Highgate has been high on my list to visit as some of my father’s photos from 1948 are of the pubs and buildings around the centre of Highgate and with the recent good weather, a destination with a pub seemed perfect.

Highgate is probably better known for the cemetery of the same name, however the village at the top of the hill is well worth a visit to view some of the architecture and stop at some of the many pubs.

Coming out of London, up Highgate West Hill, after a long climb up to the heights of Highgate we reach the Flask. This is how the Flask looked in 1948:

And my April 2015 photo shows the pub looking very much the same:

It is really good that in the intervening 67 years there has not been too much change to the pub. The main difference being the courtyard area in front which is now a seating area, although in the 1948 photo you can just see some tables and chairs to the right and left of the courtyard so perhaps even this has not changed that significantly.

Internally, the pub has avoided the conversion to a large open space, the fate of so many other pubs. The Flask still has many small bar areas and rooms at different levels and is probably much the same as when my father visited in 1948.

The name of the pub is apparently from the flasks that were sold from the pub to collect water from the local springs.

Hogarth allegedly drank at the Flask. From Old and New London:

“During his apprenticeship he made an excursion to this favourite spot with three of his companions. The weather being sultry, they went into a public-house on the Green, where they had not been long, before a quarrel arose between two persons in the same room, when, one of the disputants having struck his opponent with a quart pot he had in his hand, and cut him very much, causing him to make a most hideous grin, the humourist could not refrain from taking out his pencil and sketching one of the most ludicrous scenes imaginable, and what rendered it the more valuable was that it exhibited the exact likeness of all present.”

Fortunately the Flask was very peaceful during my visit, and it was the perfect location to enjoy the spring sunshine.

Another view of the Flask from the side, passing along Highgate West Hill in 1948:

And today in April 2015:

The Flask is now a Fuller’s pub. In 1948 as can be seen from the sign above the entrance it sold Taylor Walker’s Prize Beers. Taylor Walker was founded in Stepney, East London in 1739 and originally brewed beer in Limehouse. It has been through a number of changes in ownership and is now a brand owned by Spirit Pub Company. At some point since 1948, it was acquired by Fullers who still brew beer in Chiswick, West London.

Part of the Green referred to in the Hogarth reference is still in front of the Flask and gives the impression of being in a country village rather than north London:

The direction sign gives the very stark choice of either entering Highgate Village or going to the North. Highgate obviously has a very low opinion of the value of visiting anywhere else in the local area.

Leaving the Flask and completing the walk up the hill, we find another pub, the Gatehouse. Highgate does seem well provided with pubs. In 1826, Old and New London records that there were nineteen licensed taverns. The pubs of Highgate practiced a custom whereby strangers visiting a pub had to swear an oath on a set of animal horns (each pub having their own). Byron referred to the ceremony in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage:

“Some o’er thy Thamis row the ribboned fair,

Others along the safer turnpike fly;

Some Richmond Hill ascend, some scud to Ware,

And many to the steep of Highgate hie.

Ask ye, Boeotian shades, the reason why?

‘Tis to the worship of the solemn Horn,

Grasped in the holy hand of Mystery,

In whose dread name both men and maids are sworn,

And consecrate the oath with draught and dance till morn.”

The custom died out in the 19th century.

I did not count how many are there today, but there does still seem to be a good number.

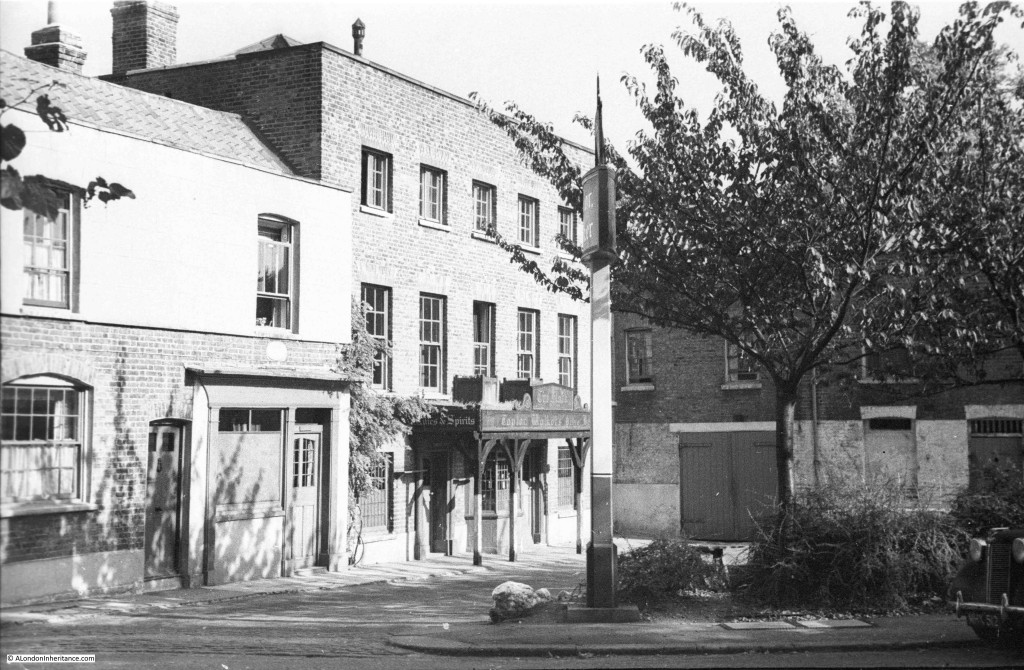

This is my father’s photo of the Gatehouse from 1948:

And from the same location in 2015:

In 67 years it is remarkable how little change there has been, apart from the style of cars, it is mainly cosmetic.

The Gatehouse may look relatively new, however this is one of the key locations in Highgate and the Gatehouse has a long history.

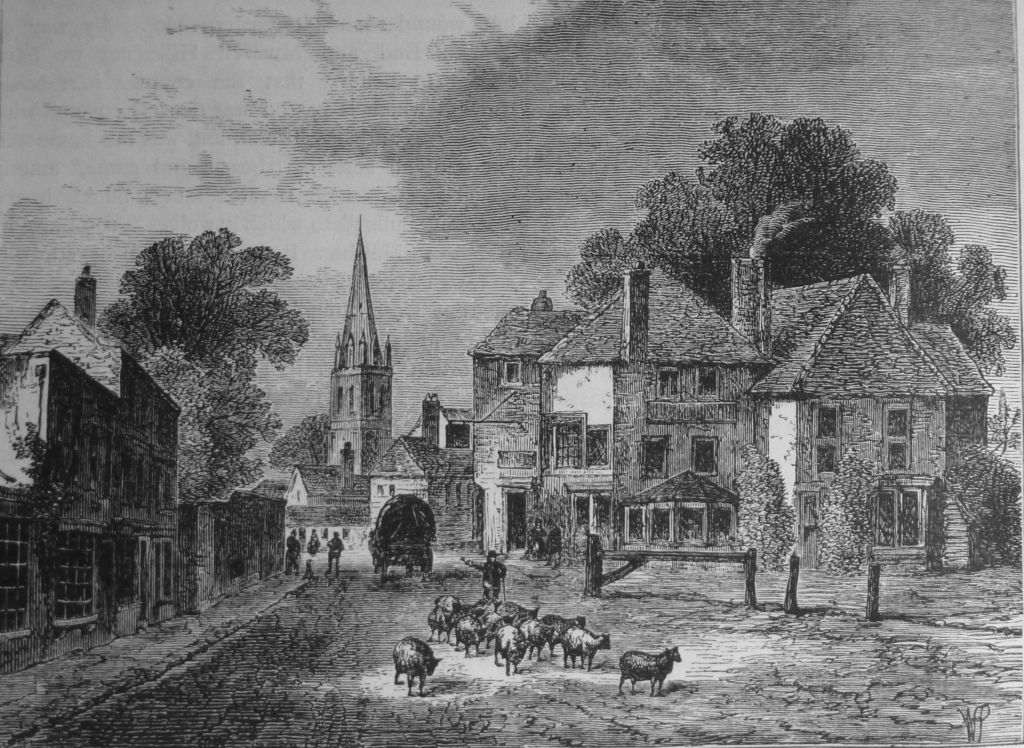

The name Highgate was first recorded in the 14th century, and refers to one of the Gates that provided access to the park, owned by the Bishop of London that stretched from Highgate, to the Spaniards pub in Hampstead and to East Finchley. There is also a view that the name has an earlier source and is based on “haeg”, the Saxon word for a hedge, where a hedge would also have been used to fence around a park.

At some point early in the 14th century, the Bishops of London had allowed a route through their parkland which due to the height of the land around Highgate, provided a more passable route in winter than the main route north through Crouch End and up to Muswell Hill.

The Gate here, or Gatehouse was to collect tolls from travellers along this route and is on the site of the earliest recorded building in Highgate.

The Gatehouse in 1820:

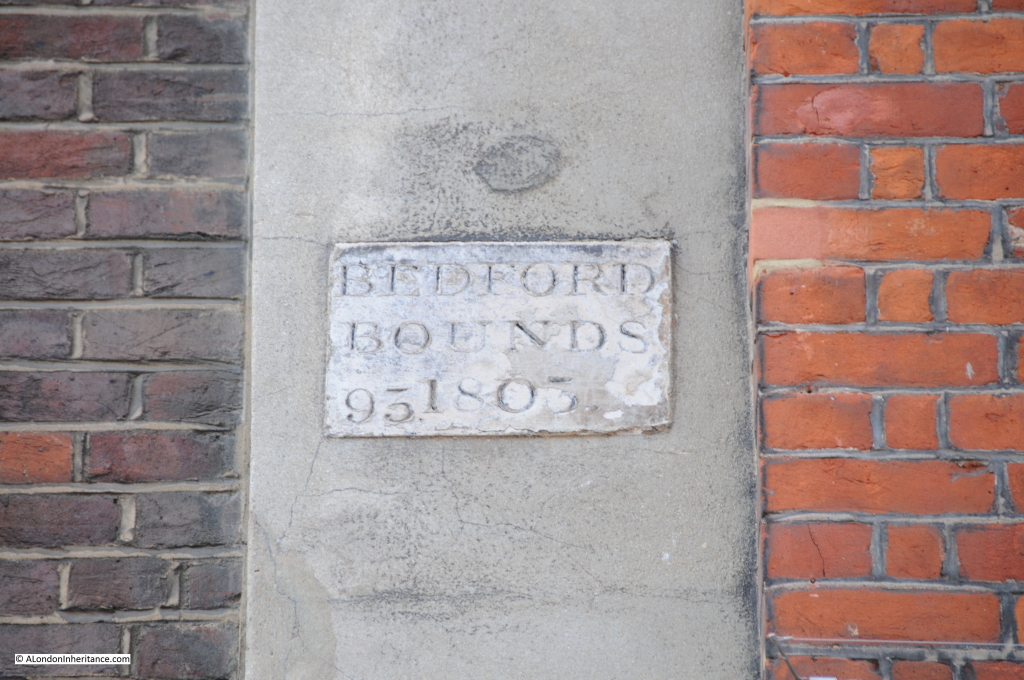

The Gatehouse also stood in two different parishes as evident from the parish boundary markers still found on the wall of the building:

The Gatehouse was split between the Parish of Hornsey and St. Pancras Parish. Being split between two parishes caused problems during some of the functions performed within the building. When used as a court, a rope had to be strung across the floor to divide into the two parishes and ensure that the prisoner did not escape into the other parish.

Boundary changes in 1994 took the whole of the building into the London Borough of Camden.

The gates that gave the Gatehouse its name were removed in 1892 with tolls having finished a few years earlier in 1876.

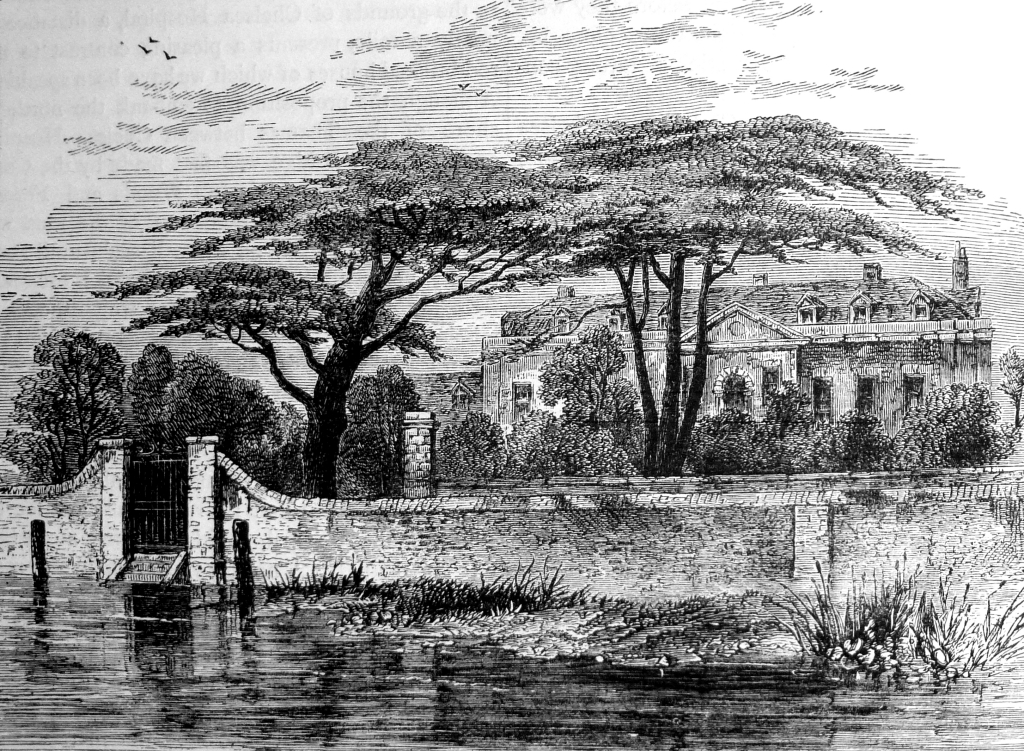

The location of Highgate, on hills to the north of London made it a popular location to live, close to London, but just far enough away to avoid the dense population, pollution, smoke, smells etc. of the city. There was much development of Highgate in the 18th and 19th centuries and many of these buildings remain today.

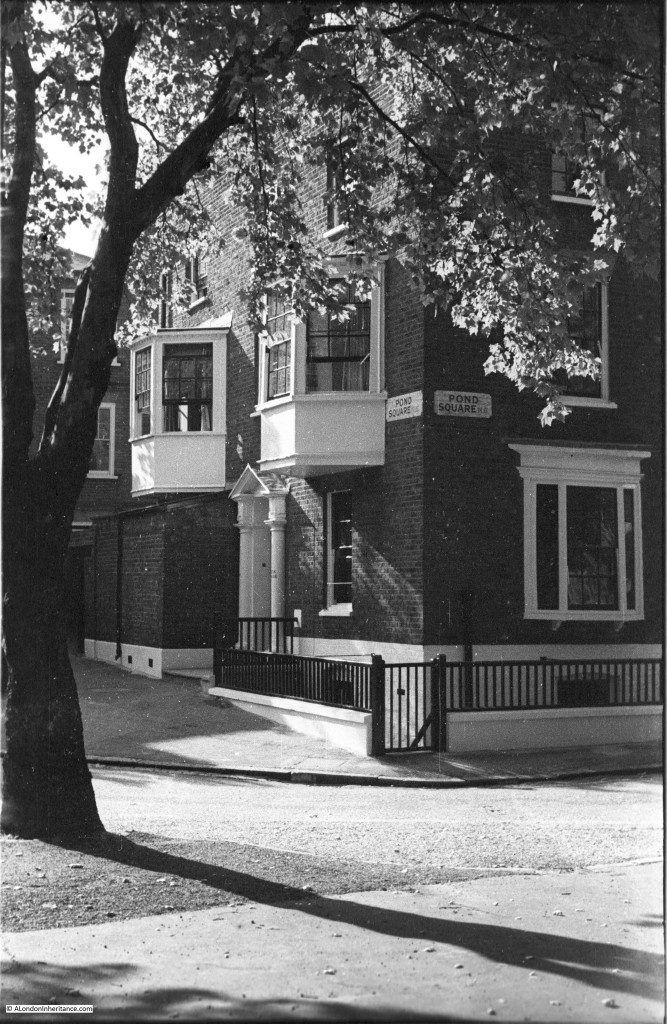

Close to the Gatehouse is Pond Square. My father took this photo in 1948:

And in 2015, remove the scaffolding and the building is much the same.

The name Pond Square comes from the ponds that were originally in the centre area of the square. The ponds were created by the digging of gravel for maintenance of the roads, however the ponds were filled in during the mid 19th century due to the poor state of the ponds and the associated risks to health (being also used as cesspools).

Looking across Pond Square today, there is no evidence of the ponds, although there is still evidence of what Ian Nairn described in Nairn’s London as:

“Ruined by traffic and a weary flow of municipal improvements – asphalt and crazy walling – which is at its worst in Pond Square. The place could be transformed without altering anything but the surface of the floor.”

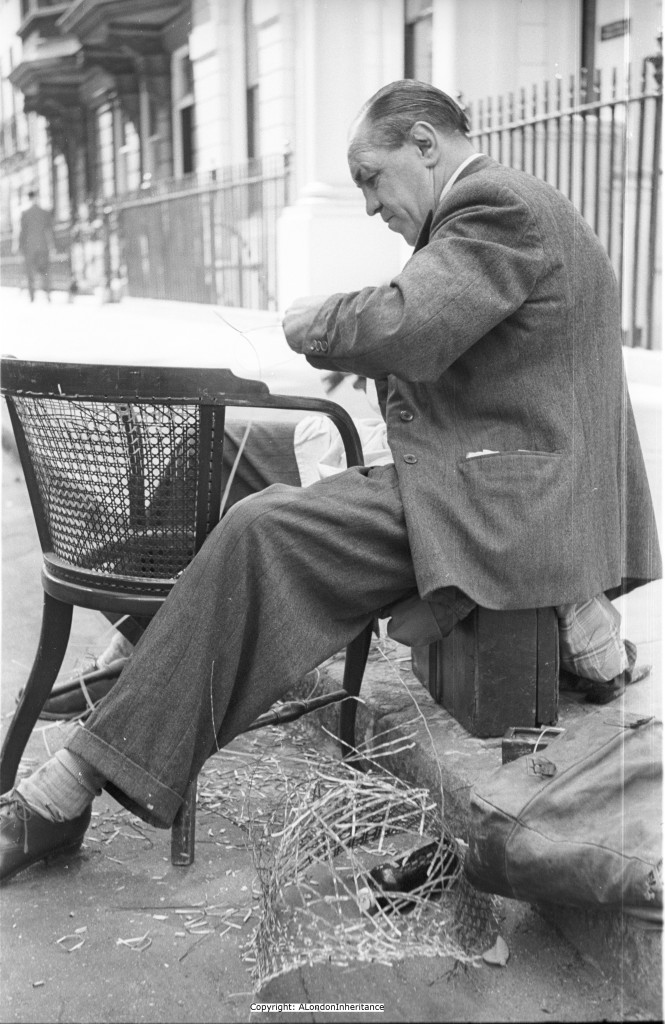

Walking round Highgate I was really pleased to find the location of the following photo. This is one of the many that I was not sure if I would find the location. There is no information, street names, recognisable buildings etc. to identify the location of the photo. It was on a strip of negatives that had one Highgate photo but also had photos of central London.

This is Southwood Lane looking up into Highgate, and in 2015 it is remarkably much the same:

Highgate is a fascinating location to visit and as shown by the photos my father took in 1948 and my 2015 photos has changed very little.

As usual, in the space of a weekly blog I have only been able to scratch the surface of the history of Highgate, but it is a location I will certainly be back to explore again.