In 2020 I wrote a couple of posts on City of London pubs. It was in the middle of the Covid pandemic, and between a couple of lock downs I walked a very quiet City of London, photographing all the old pubs. A project based on what I have learnt from exploring all my father’s photos – it is the ordinary that changes so quickly, and we seldom notice trends or significant changes until they have happened.

Since that post, just three years ago, three pubs have closed. The White Swan in Fetter Lane has been demolished, the Tipperary in Fleet Street has been closed for some time and it is doubtful if it will reopen, and the latest pub to close is the St. Bride’s Tavern in Bridewell Place, which I photographed a couple of weeks ago:

It was not down to a post pandemic lack of trade, or any financial problems with the pub, it was that the owner of the property would not let the pub renew the lease in January 2023, so the pub closed on Friday the 23rd of December 2022.

The owner of the land plans to strip back the office block to the right of the pub in the above photo, demolish the pub, and rebuild the building on the right with a new extension where the St. Bride’s Tavern is now located. to create a much large office block.

There was a well supported application to the City of London Environment Department to nominate the St. Bride’s Tavern as an Asset of Community Value, however this did not work, and closure went ahead.

With the trend of recent years for greater working from home, and a general decline in the need for office space, I really do wonder why establishments such as the St. Bride’s Tavern need to be demolished to create new office space.

The City of London was also planning to pivot more towards heritage, culture, arts and tourism as a response to post pandemic working, and retaining pubs would align with this strategy, however the City is being reasonably successful in tempting businesses to move back to the City from Canary Wharf as companies such as HSBC let go of large office space in the Isle of Dogs, in favour of smaller offices in the City.

An image of the new development can be seen on the website of the company that secured planning approval for the development. Click here to see the news item.

The image at top left shows the smaller extension of the new development to the rear of the main building on New Bridge Street, and the details of the development include the statement that there will be a “re-provided public house at ground-floor and part-basement level”, however a pub as part of the ground floor and basement of a modern office block just does not have the character and attraction of a dedicated building.

The building in which the St. Bride’s Tavern was located is not particularly attractive. A post-war development, which does have a rather unusual central bay of windows that runs up to include the second floor. This always looked good in the evening when the bay windows were lit.

The following photo shows St. Bride’s Tavern when it was open back in 2020:

Decoration at the top of the bay windows:

The pub sign has been removed, however I did photograph the sign back in 2020, which showed the tower of the church after which the pub was named:

The pub is a post war building as the pre-war buildings on the site had been damaged during the war.

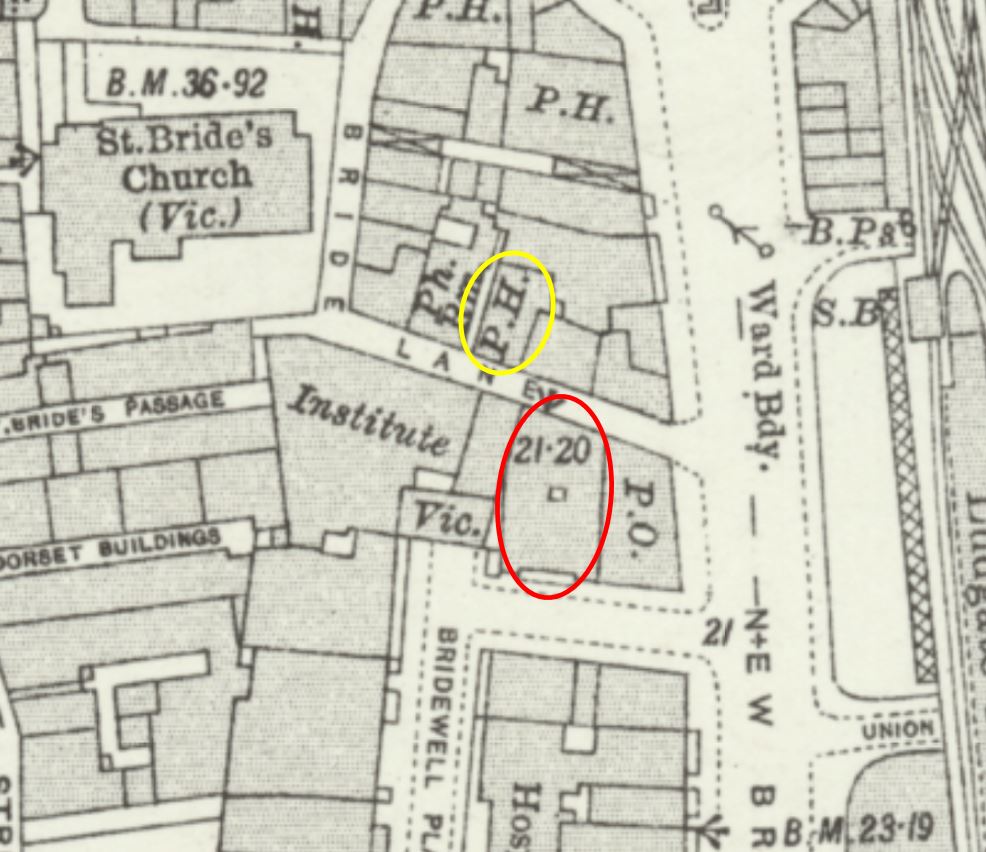

I am not sure that the site of the pub today is the original site of the pub as in the 1894 Ordnance Survey map it was not marked as a Public House and the building on the site appears to have been occupied by a Police Station of the 3rd Division.

Searching through old newspaper reports about the pub and a St. Bride’s Tavern appears to have been in the street behind the current pub – Bride Lane, for example in the Daily News on Saturday October the 19th, 1901, the pub was up for sale: “Freehold ground rent of £100 per annum, exceptionally well secured upon those fully-licensed premises, licensed as the White Boar, but also known as the St. Bride’s Tavern, Bride-lane, Fleet-street”.

Also, in the East London Observer on the 8th of December, 1900, there was a report on the marriage of Charles Seaward who was the Licensed Victualler of the Drum and Monkey pub in Whitecross-street and Miss Clara C. Wilkins, the manageress of the St. Bride’s Tavern, Bride-lane, Ludgate Circus. The wedding took place at St. Bride’s Church and the wedding breakfast was held in the St. Bride’s Tavern, from where the newly married couple would leave, later in the day, for a honeymoon in Brighton.

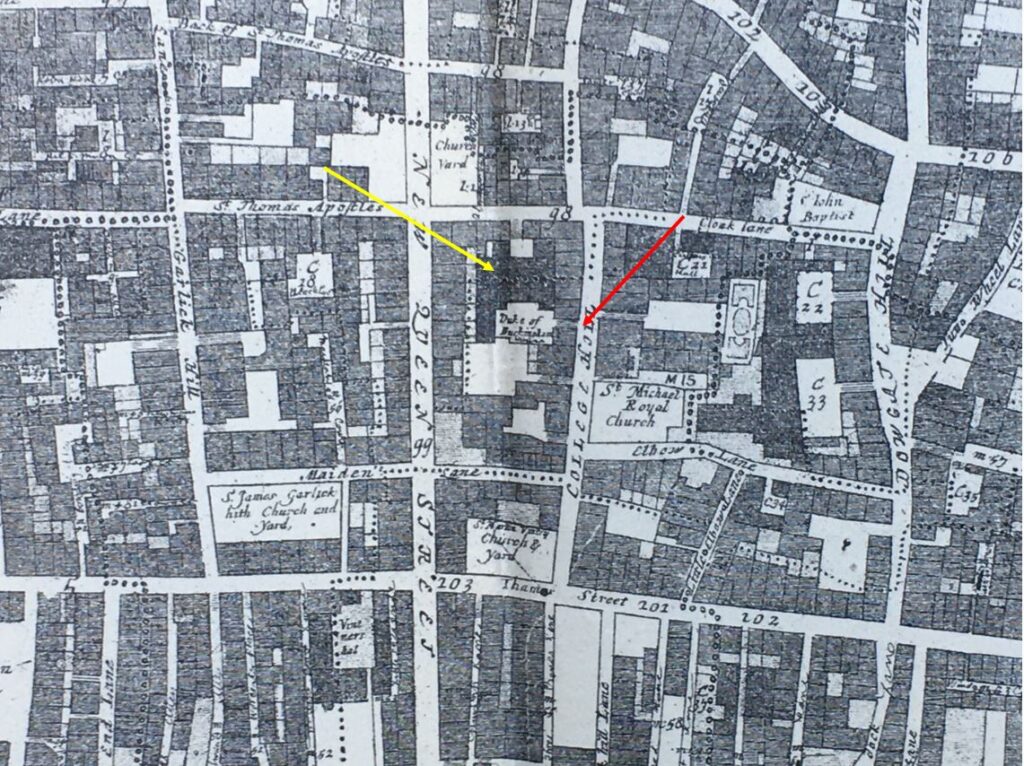

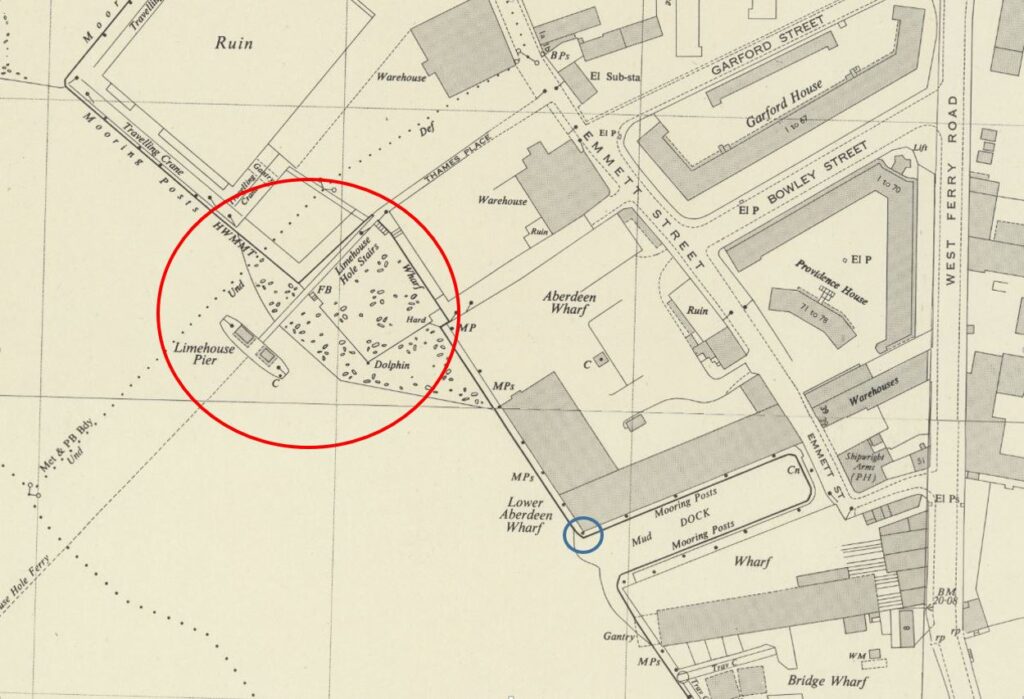

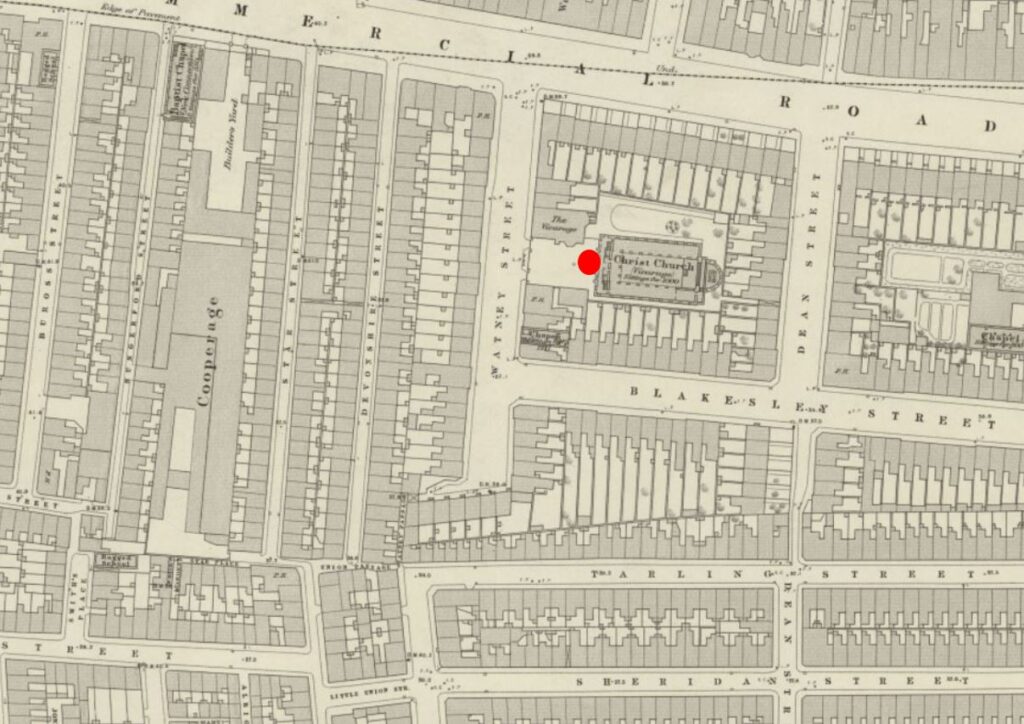

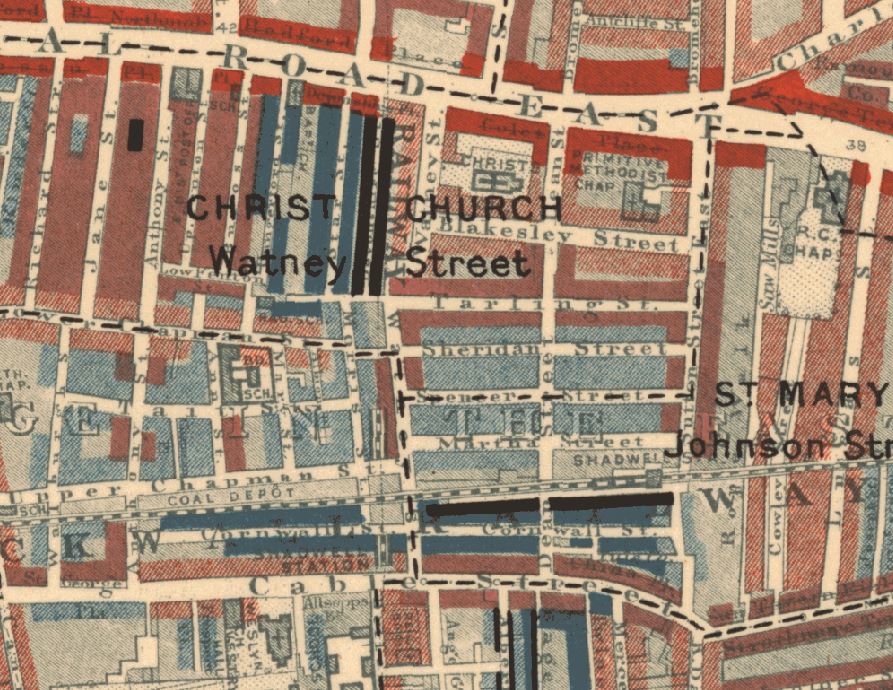

In the following extract from the 1894 OS map, I have ringed the current site of the St. Bride’s Tavern in red (and not labelled as a public house), and the pub that I believe was the original White Boar / St. Bride’s Tavern in yellow, and in the 1951 revision of the OS map, the pub in Bride Lane is still marked, with the space of the current pub an empty space (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

The current St. Bride’s Tavern building does extend all the way between Bridewell Place and Bride Lane, so I suspect that the original pub may have wanted a larger site, and had available the land almost directly opposite, with the new pub still retaining an aspect (although the rear) onto Bride Lane.

If the site of the current pub was also the site of the original, it would have faced onto Bride Lane so could have had that address, but it was not marked as a public house in the OS map.

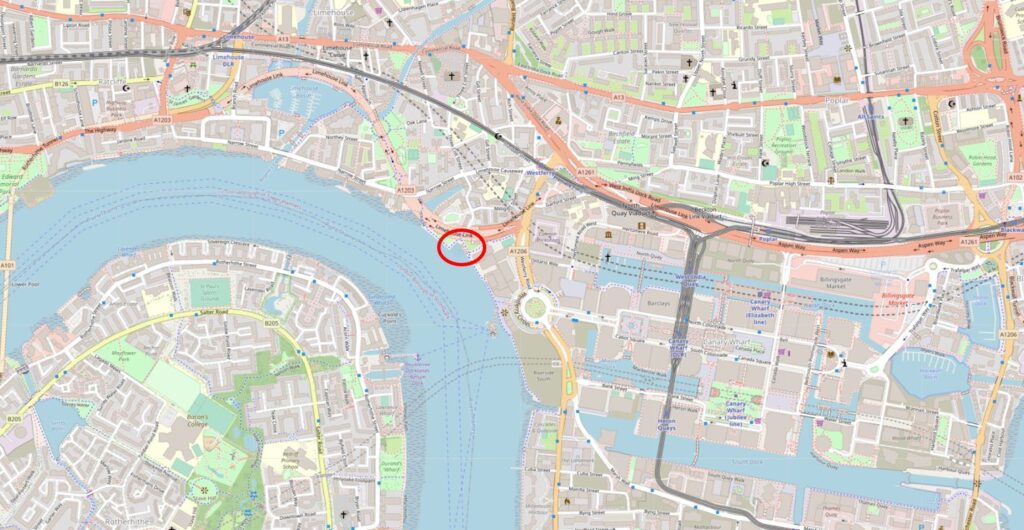

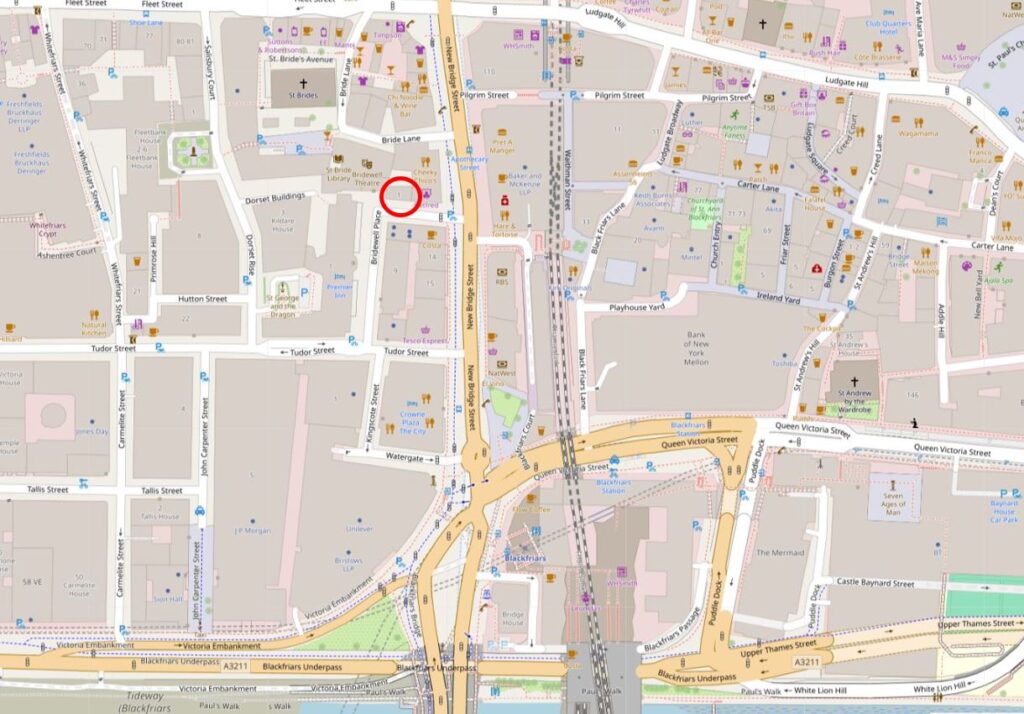

I have marked the site today of the pub with a red circle in the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

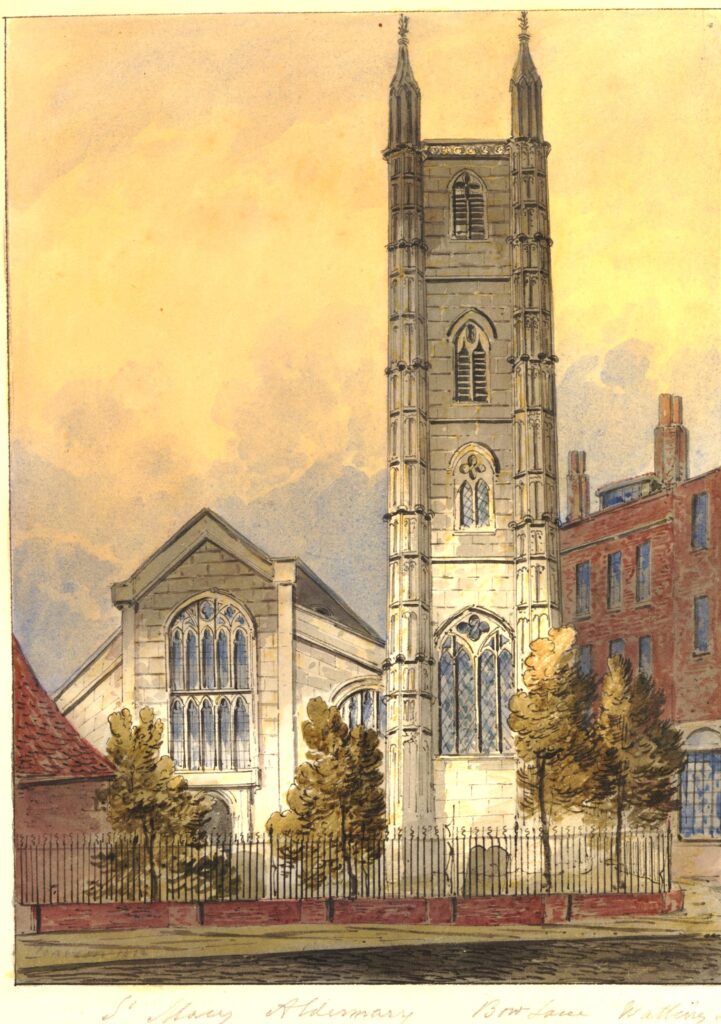

The St. Bride’s Tavern is named after the nearby church, as the image on the pub sign confirms, however the pub is in Bridewell Place, which is a very historic name and location.

The name Bridewell originally came from a well between Fleet Street and the Thames, which was dedicated to St. Bride. The name Bridewell was also given to what was described as a “stately and beautiful house” built by Henry VIII in 1522.

London Past and Present, by Henry B. Wheatley (1891) provides the following information: “Built by Henry VIII in the year 1522 for the reception of Charles V of Spain. Charles himself was lodged at Blackfriars, but his nobles in this new built Bridewell, ‘a gallery being made out of the house over the water (the Fleet) and through the wall of the City into the Emperor’s lodgings at the Blackfriars”

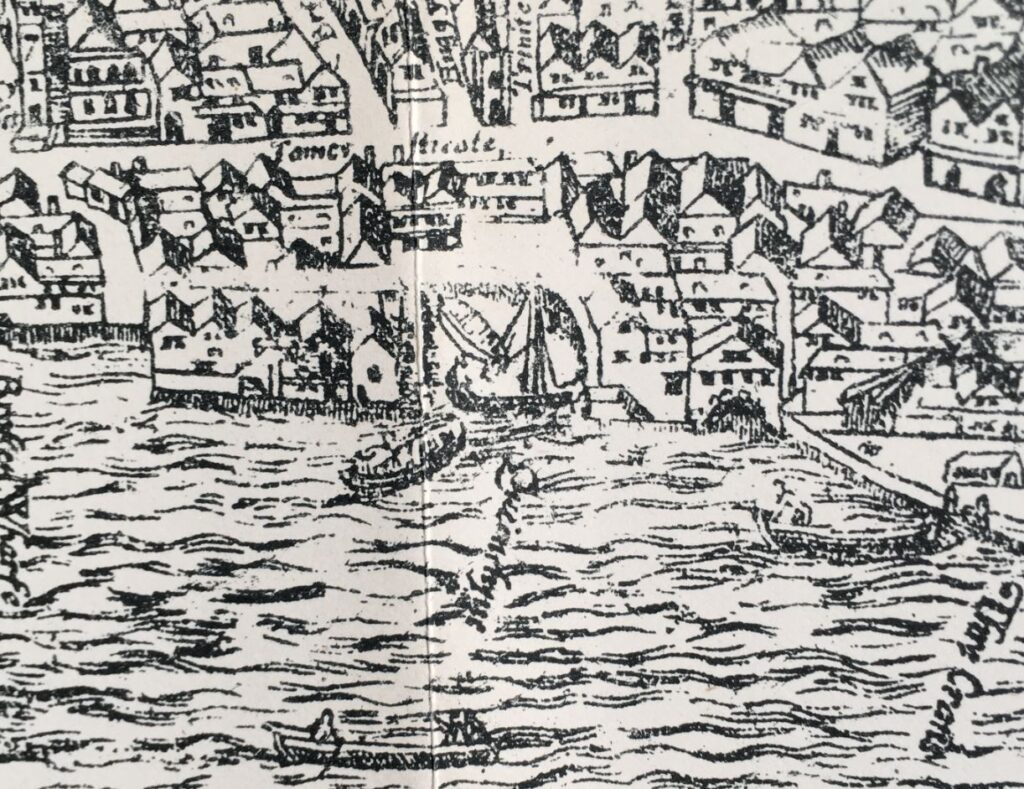

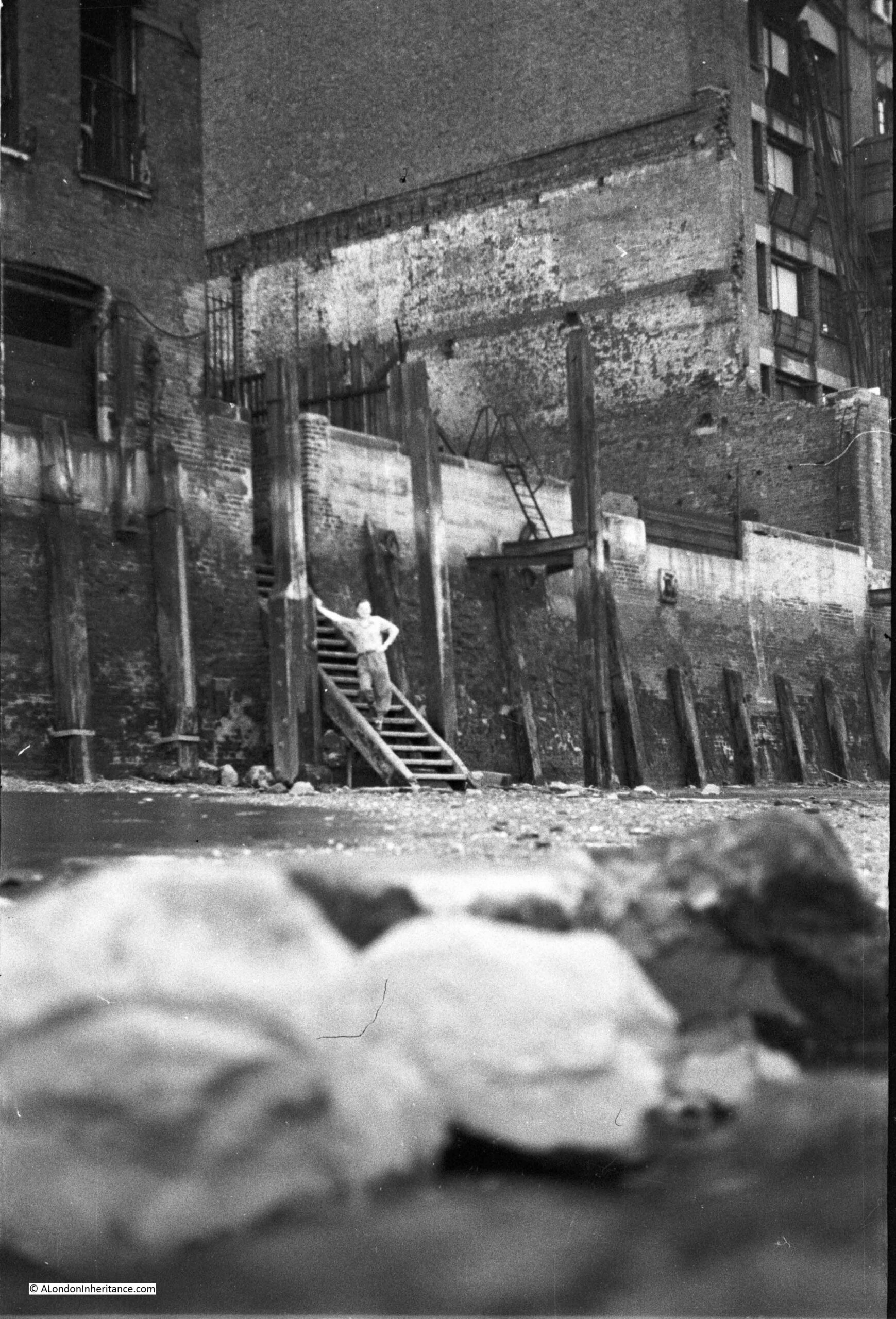

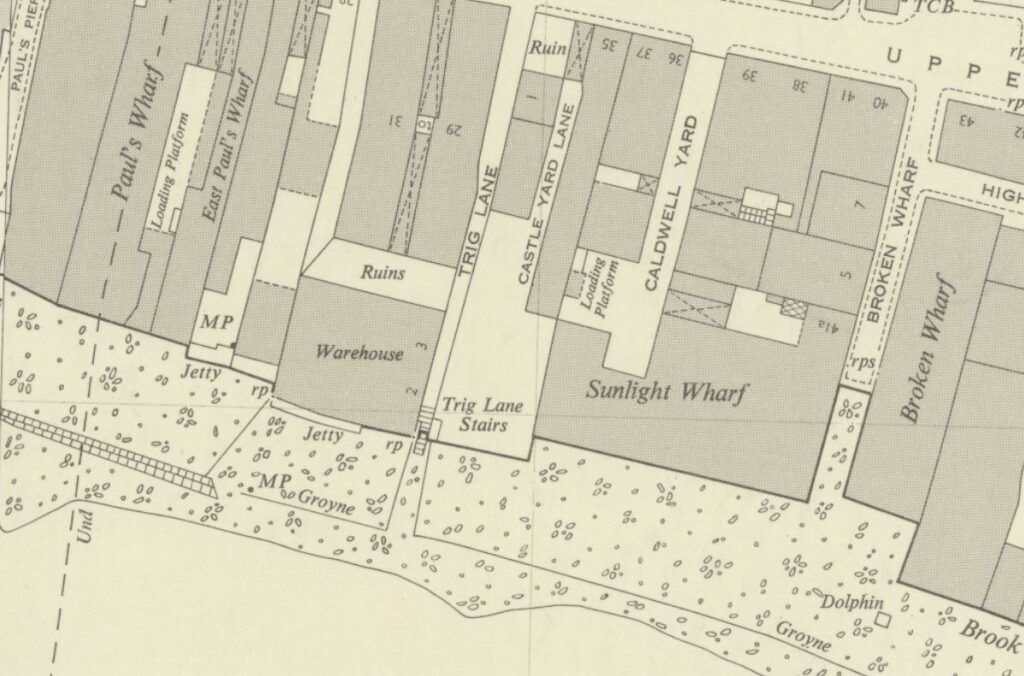

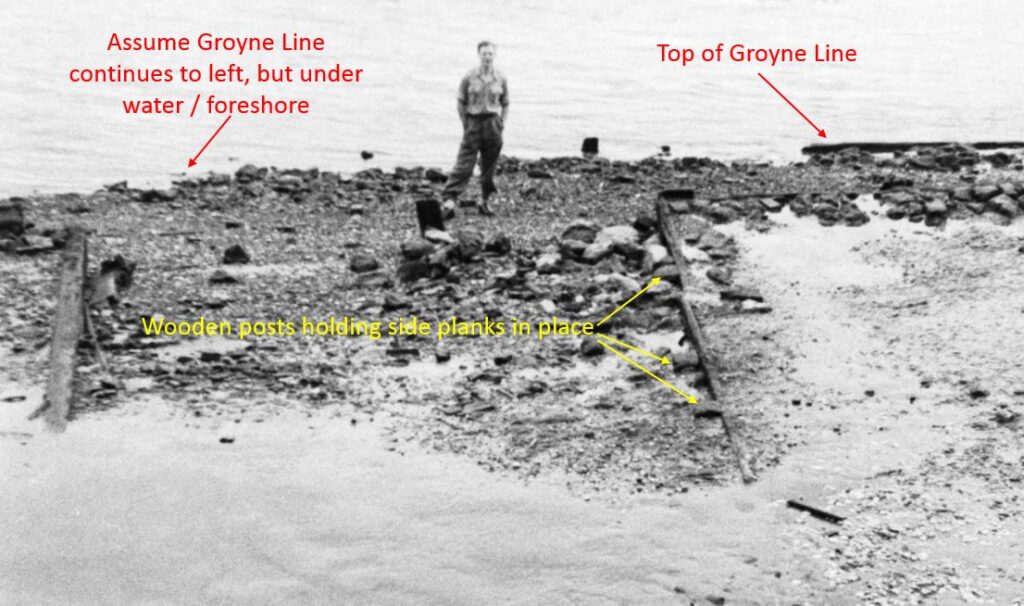

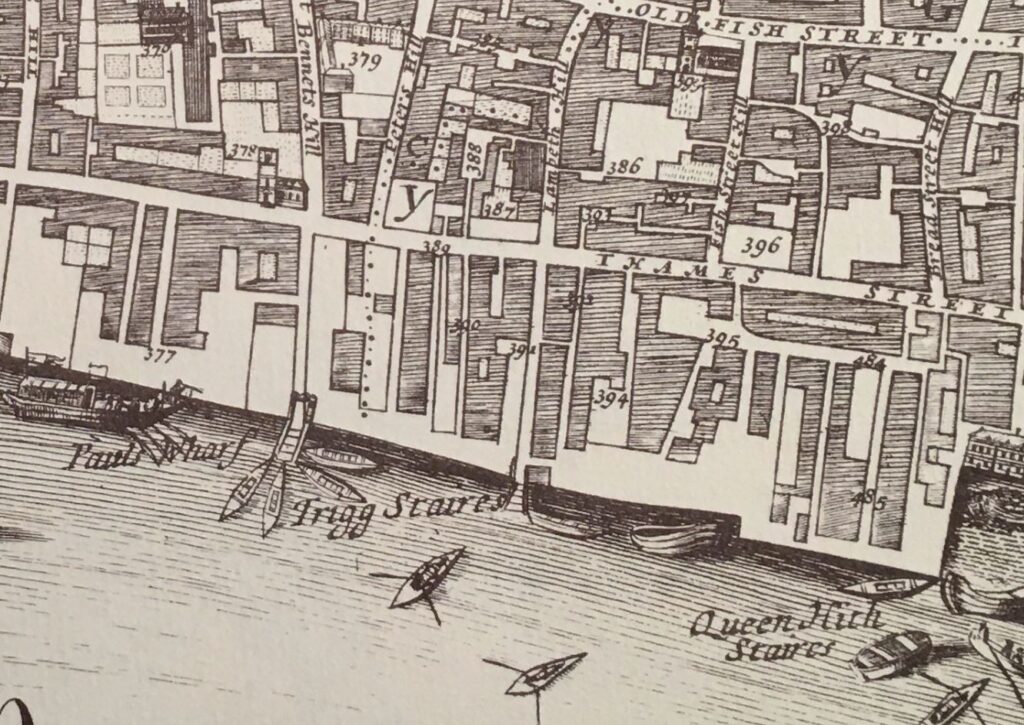

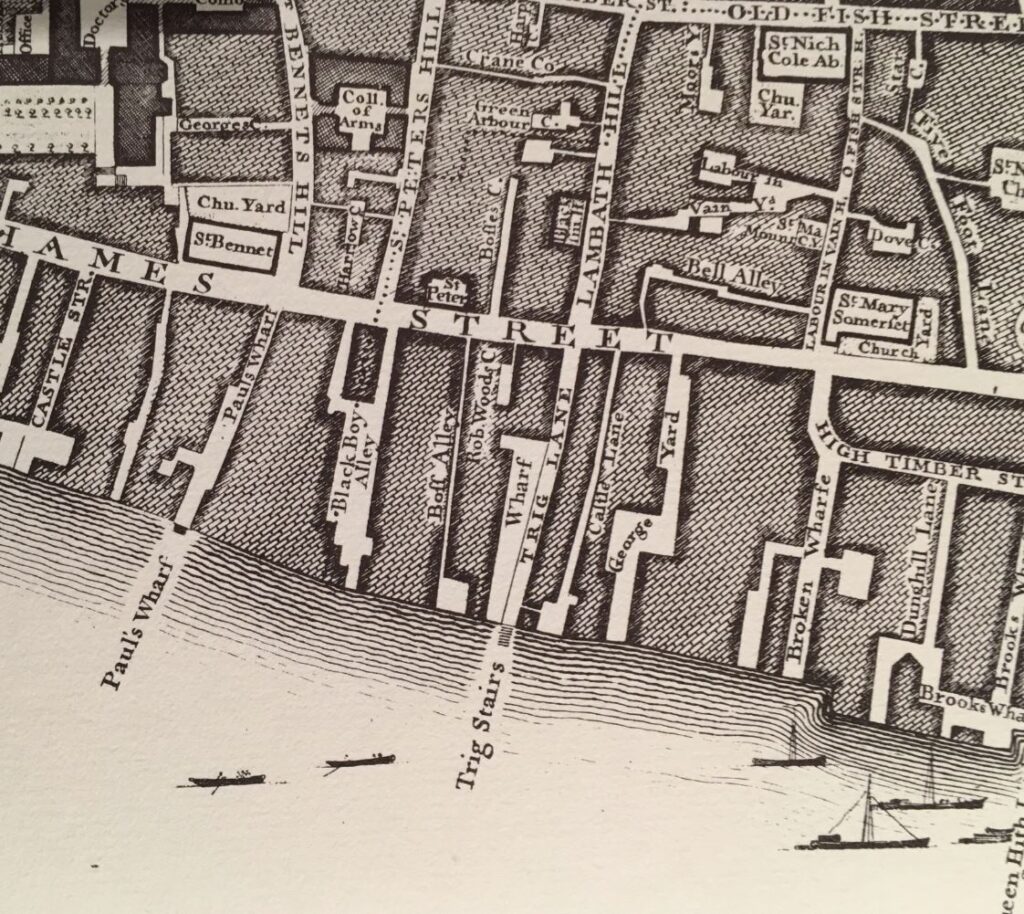

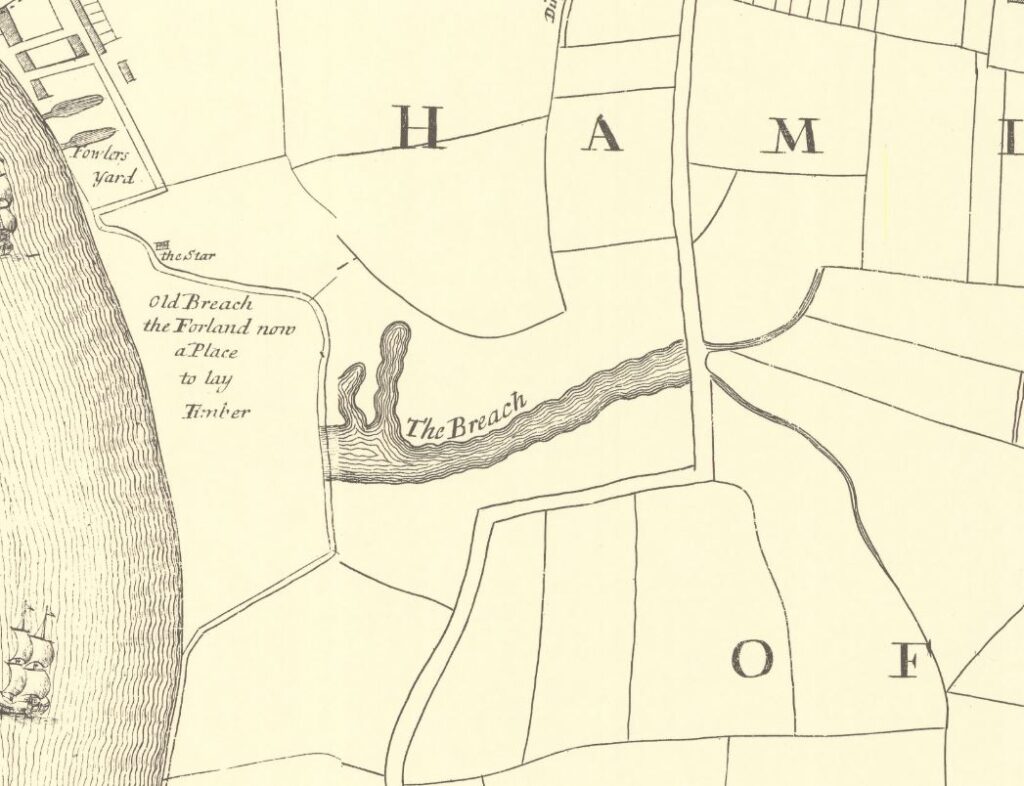

The Agas map includes an image of Bridewell, alongside the Fleet and part of which looked onto the Thames. In the 16th century the bank of the river was further in land than the river is today:

The following print from 1818 shows Bridewell Palace as it appeared in 1660 ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

We can see what was by the 17th century, the narrow entrance to the Fleet, Bridewell on the left bank and part of Blackfriars on the right.

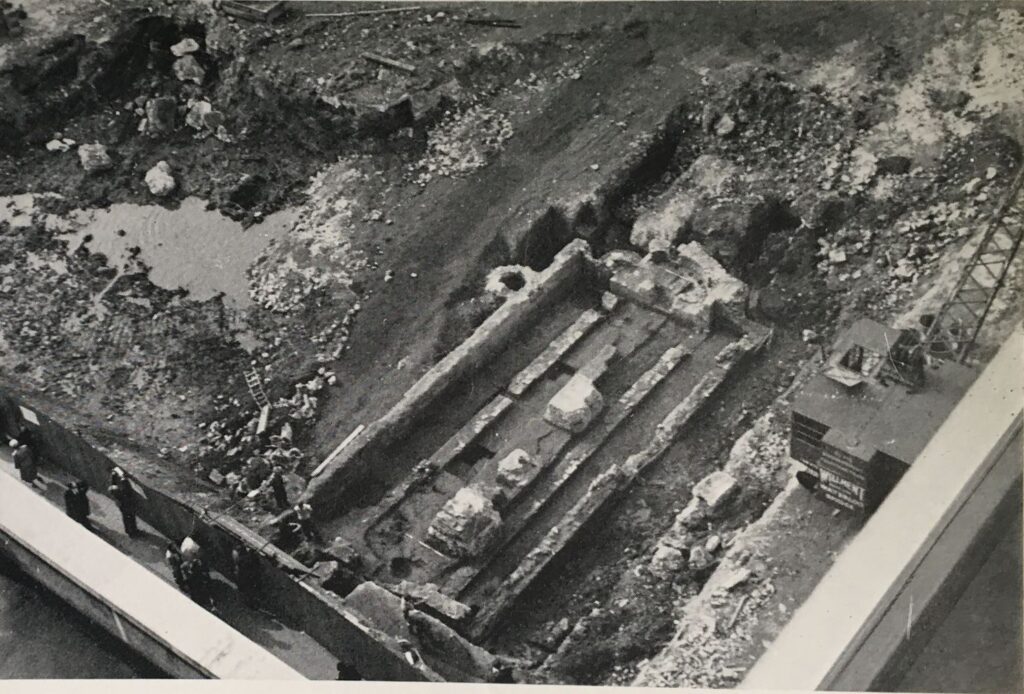

The print provides the following background: “Bridewell in its original state , was a building of considerable magnitude, as well as grandeur, extending from the banks of the Thames southward, as far north as the present Bride Lane, and having a noble castellated front towards the river, the interior was divided into different squares or courts with cloisters, gardens &c. as represented in the vignette. King Henry VIII built this Palace for the entertainment of the Emperor Charles V, but it retained the dignity of a Royal residence only during the former, being converted into an Hospital by Edward VI who gave it to the City for the maintenance and employment of vagrants and Idle Persons and of Poor Boys uniting it in one cooperation with Bethlem Hospital. A very small part of the original structure now remains.”

So if Henry VIII’s Bridewell extended as far north as Bride Lane, then the St. Bride’s Tavern of today is located inside the very northern edge of the old palace.

London Past and Present, by Henry B. Wheatley (1891) provides the following regarding the change in use of the building: “Bridewell, a manor or house, so called – presented to the City of London by King Edward VI, after an appeal through Mr. Secretary Cecil and a sermon by Bishop Ridley, who begged it of the King as a workhouse for the Poor, and a house of Correction ‘for the strumpet and idle person, for the rioter that consumeth all, and for the vagabond that will abide in no place”.

The problem for the new institution was that the availability of food and lodgings in the workhouse attracted people from across London, and it was “found to be a serious inconvenience. Idle and abandoned people from the outskirts of London and parts adjacent, under colour of seeking an asylum in the new institution, settled in London in great numbers, to the great annoyance of the graver residents.”

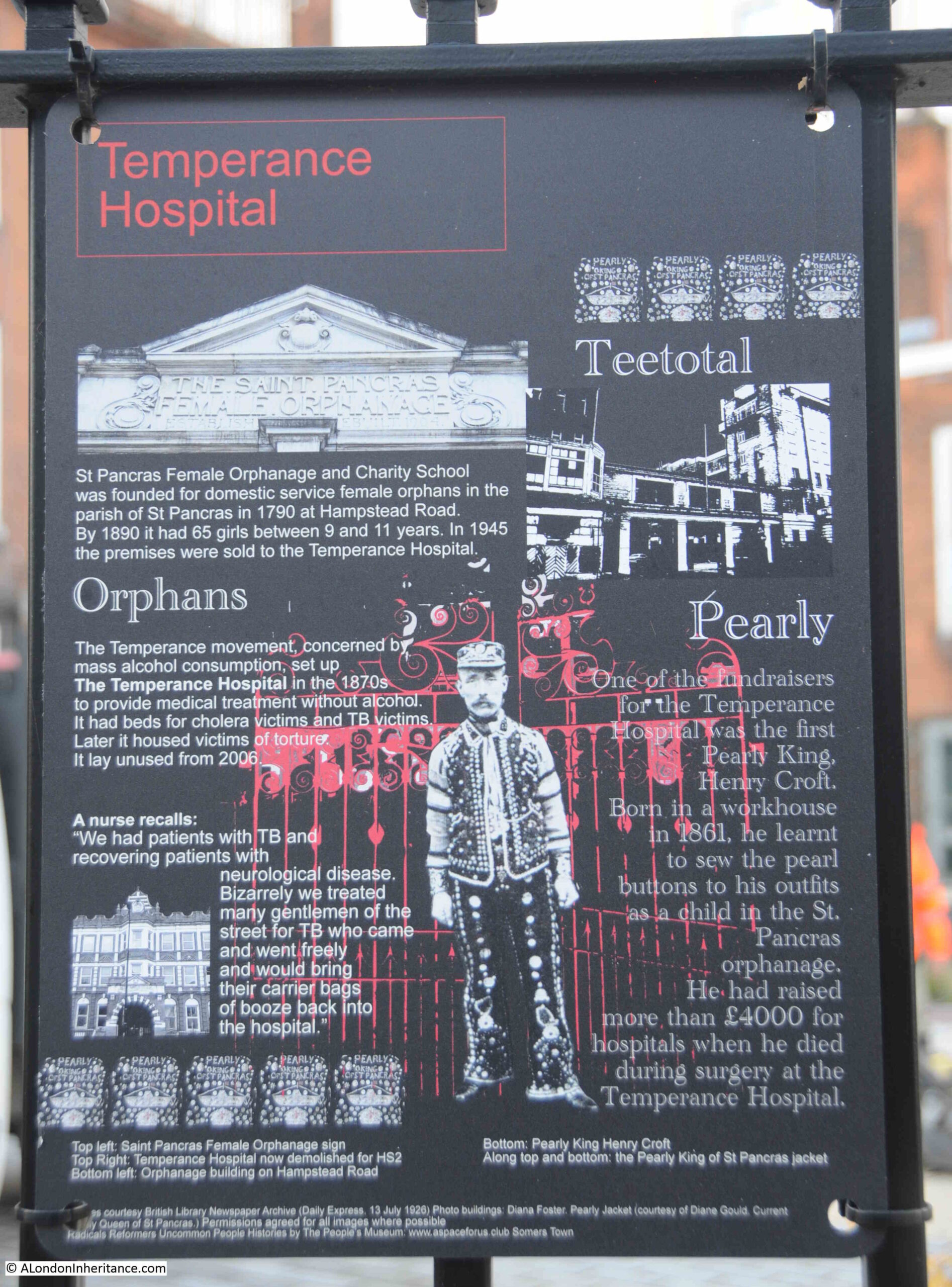

A number of children that were housed at Bridewell ended up being transported to the United States following a petition in 1618 from the Virginia Company for 100 children of the streets, who have no homes or anyone to support or provide for them. These children became part of the new colony at Jamestown.

In response to complaints about the numbers attracted to the institution, the City changed parts of the buildings of the Bridewell into a granary, however in 1666 the original house and precincts were destroyed in the Great Fire.

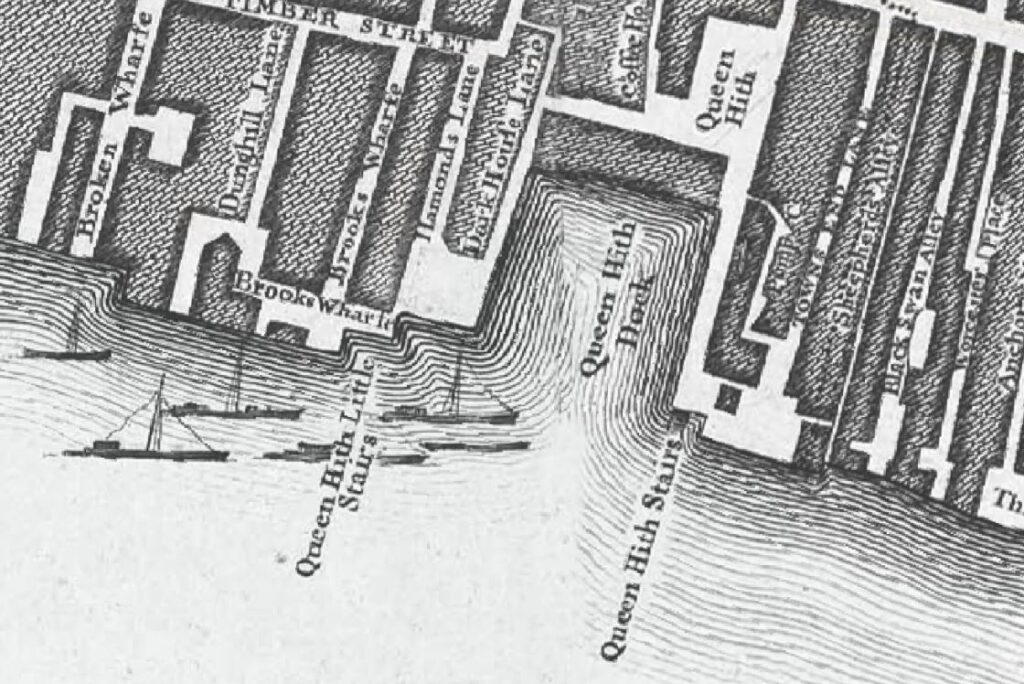

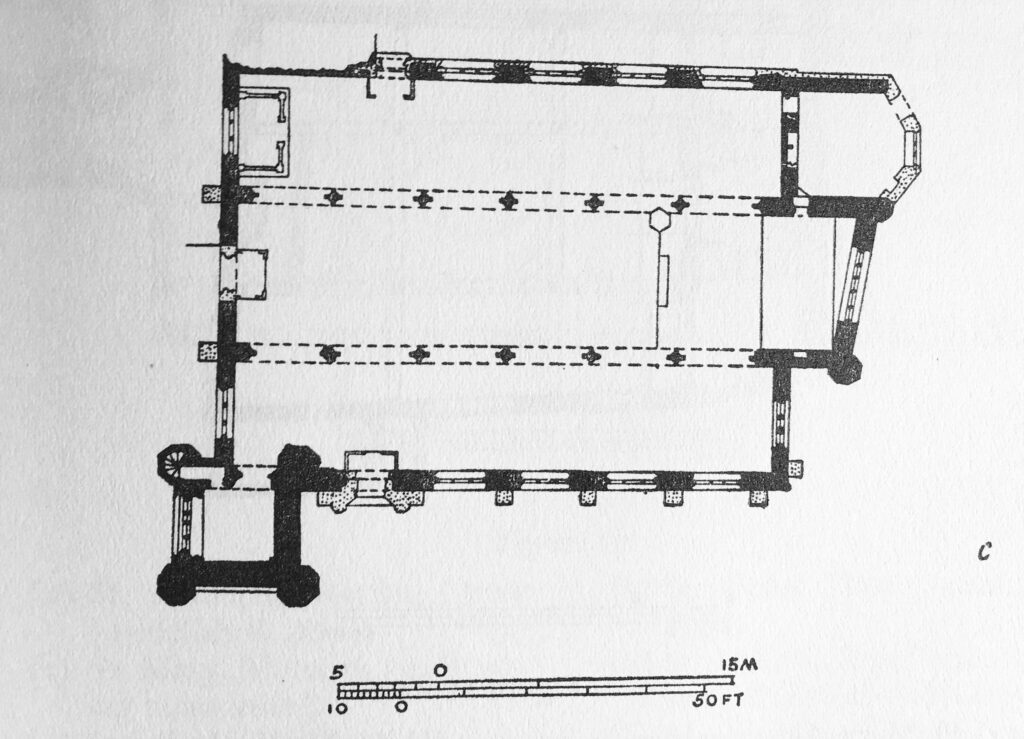

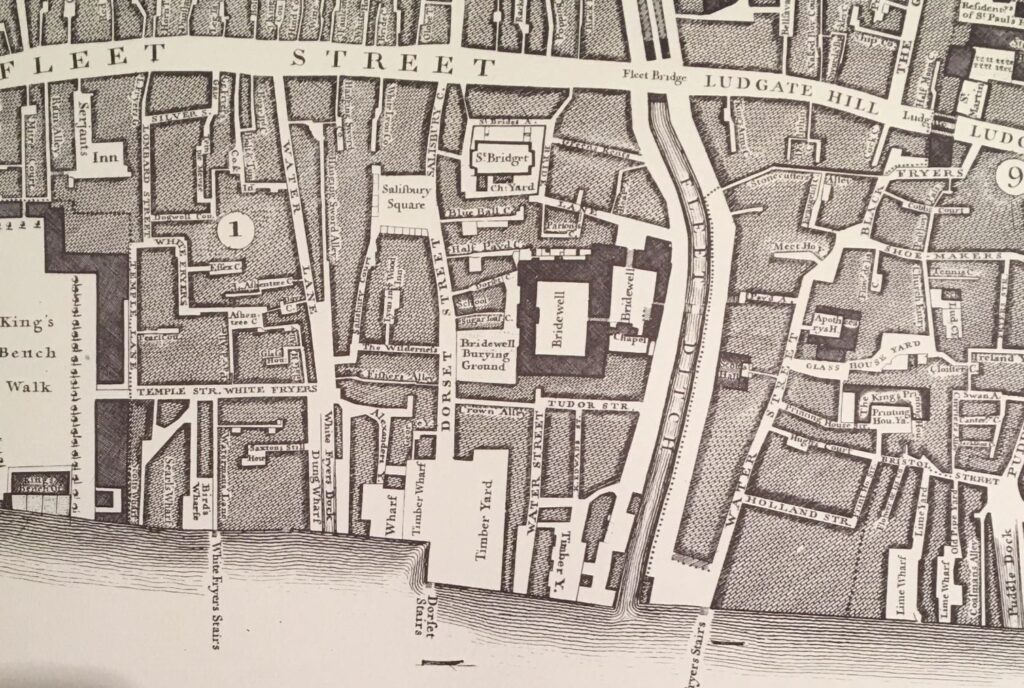

A new house was built in a “more magnificent and convenient manner than formerly”, and these new buildings, based around two central courtyards, can be seen in the centre of the following extract from Rocque’s 1746 map:

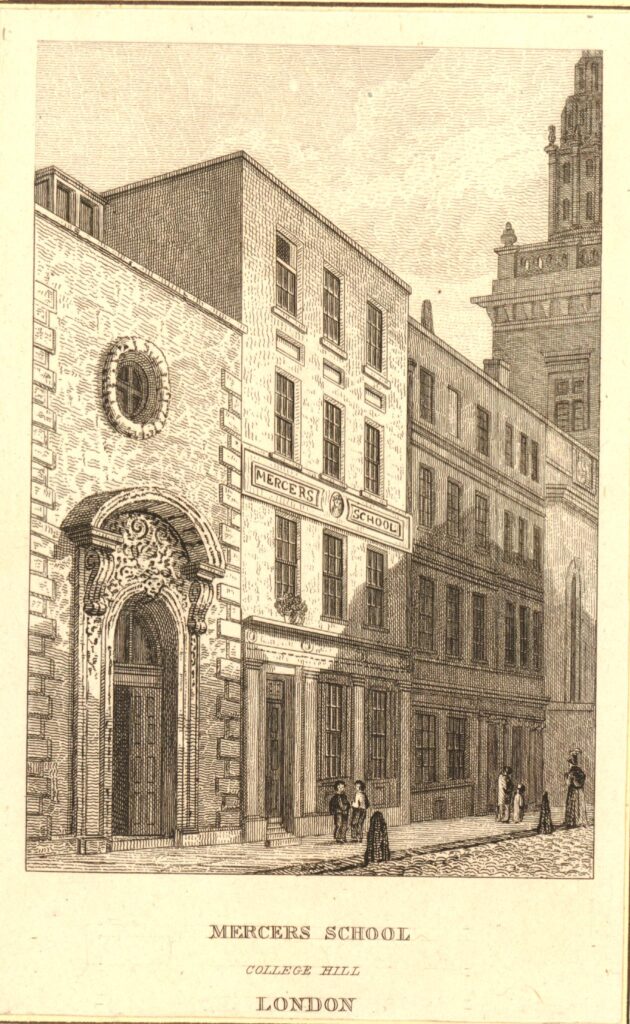

In the early 18th century, Bridewell was a place where are “maintained and brought up in the diverse arts and mysteries a considerable number of apprentices”, however “vagrants and strumpets” were still being committed into Bridewell with an average of 421 per year, with a peak of 673 in 1752.

Bridewell took on the role of a prison, and as well as holding a City Magistrates Court, the buildings also had seventy cells for male offenders and thirty for female.

Taking one year, 1743, we can get a view of some of the reasons why Londoners were being taken to Bridewell;

- Margaret Skylight (a Fortune Teller) was committed to Bridewell for stealing a pair of diamond ear rings

- On Saturday last a Man was committed to the Bridewell of this City for retailing Spirituous Liquors without a licence

- Last Wednesday Francis Karver, alias Blind Fanny was committed to Old Bridewell for hawking newspapers, not being duty stamped, contrary to Act of Parliament

- On Sunday Night last, a Parcel of Link-Men, who generally ply about Temple-Bar, made a sham Quarrel near that place, and got a great number of people together, several of whom had their pockets pick’d, by another Gang of Roques, who mingled with the Crowd, as has been very often practiced. We hear four Rogues have been since committed to Bridewell

- Yesterday James Williamson was committed to Bridewell by Mr. Alderman Arnold, for attempting to pick the Pocket of one William Burris, last Saturday Night of his Handkerchief; while he was carrying him to the Constable, one of the Gang picked his Pocket of his Watch.

I hope I have the location of all the above correct, as by the early 18th century, the name Bridewell had become a common term for a prison, or place where someone was remanded before being put up before a judge.

In London there was a Bridewell in Clerkenwell and one at Tothill Fields, Westminster, and there were several so called Bridewell’s across the country, including one at Oxford and another at Colchester.

In newspaper reports, the name was often given as Clerkenwell Bridewell or Oxford Bridewell, whereas the original establishment seems to have been referred to as simply Bridewell or Old Bridewell.

The large numbers of apprentices at Bridewell also seem to have caused much trouble in the surrounding area. They were called Bridewell Boys, and also in 1743: “On Thursday Night last about Nine o’clock, as some Bridewell Boys were coming through Shoe-lane, they attacked two women, who ran for refuge into the Salutation Tavern near Field Lane End, the Boys followed them, and to get at them, broke the glasses of the Bar, on which one of them was seized, whereupon the others retired, but soon returned in greater numbers, armed with broomsticks, &c. and demanded their Companion; which being refused, they broke all the Windows, Lamps, and whatever else they could get at; however at length, several of them were secured, and it is hoped will meet with a Punishment due to their Crime.”

Bridewell also makes an appearance in Captain Grose’s “Dictionary of Buckish Slang, University Wit and Pickpocket Eloquence”, or the “1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue”, with the term Flogging Cove, which was used to describe the beadle, or whipper, in Bridewell.

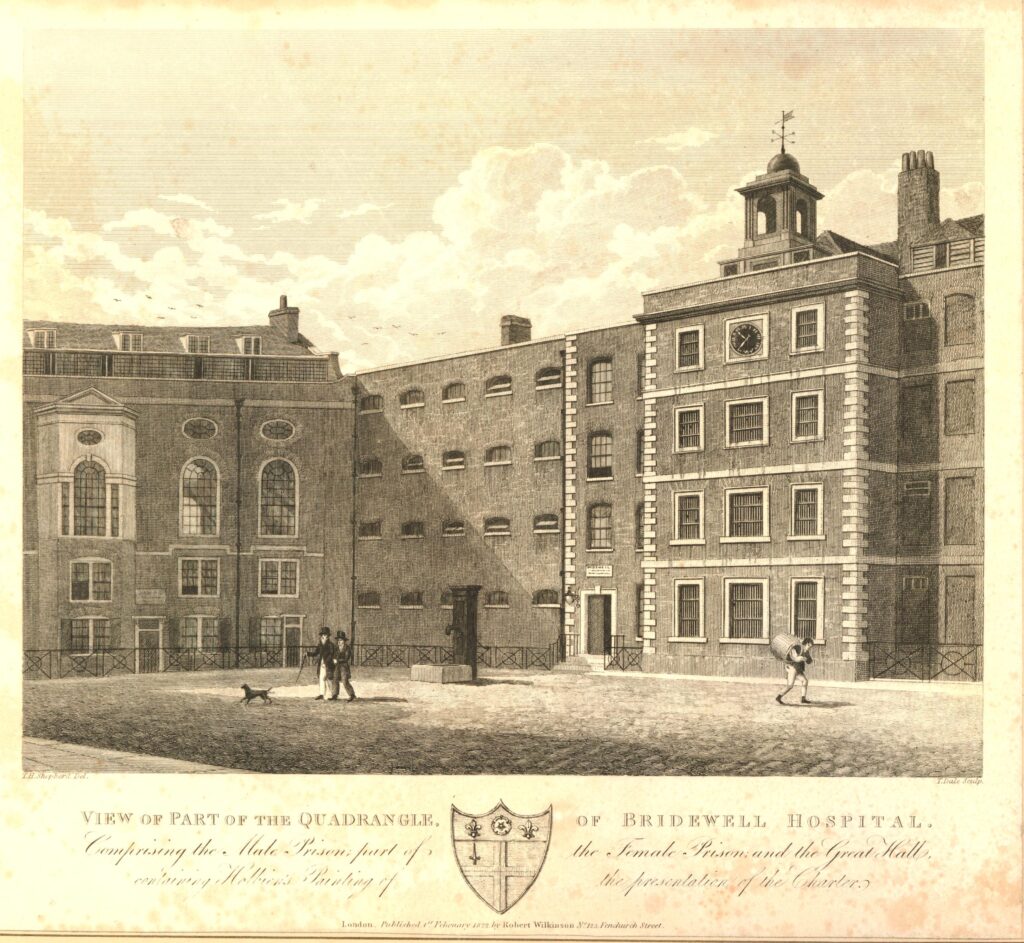

This print dating from 1822 shows part of the quadrangle at Bridewell, with the male prison, part of the female, and the Great Hall. Note the bars over the windows in the central block, and small windows in the block to the left ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

The end of Bridewell as a prison came in the 1860s when the City Prison at Holloway was built in 1863, following which, the materials of Bridewell were sold at auction and cleared away by the following year, with the chapel being demolished in 1871.

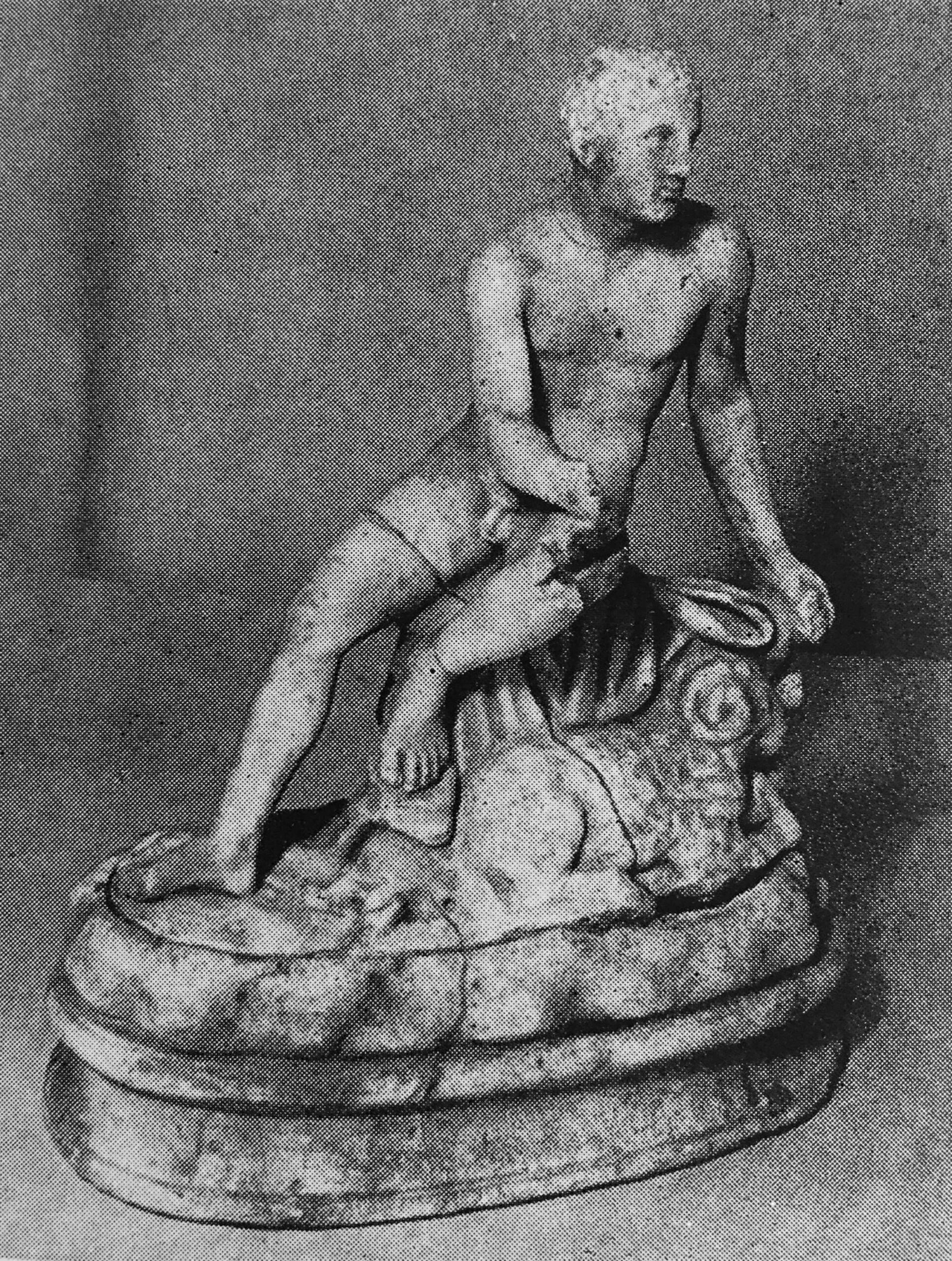

Bridewell featured in one of the prints by Hogarth in his 1732 series “A Harlot’s Progress”, and in this print we see Moll, the women featured through the series, still in her finery, as she is beating hemp, along with other inmates, under the watchful eye of a warden ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

Although Bridewell prison has long gone, the 1805 former offices of the Bridewell Prison / Hospital and entrance from New Bridge Street survives.

I have taken a photo of the building and its associated plaque several times, but cannot find them (if you knows of a cheap and efficient application for sorting and indexing thousands of digital photos, I would be really grateful), however the wonderful Geograph site came to the rescue, and the Grade II* listed building can be seen here, between the traffic lights:

Looking south down New Bridge Street cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Basher Eyre – geograph.org.uk/p/923440

The St. Bride’s Tavern will soon be similar to Bridewell – just a memory on the ever changing streets of London.

The development proposals apparently include a pub within the ground floor and basement of the new office block, but this will not be the same as the dedicated pub that currently stands on the site.

Three City of London pubs have now closed since my walk in 2020. How many more over the coming years will suffer the same fate?