Chances are, if you have walked from Waterloo Station down to the Royal Festival Hall, or the Southbank, you have walked along Sutton Walk without really being aware that you have.

Today, Sutton Walk is a short stretch of pedestrian walkway through one of the rail arches under the rail tracks leading up to Hungerford Bridge, however it was once a short street leading down to the Lion Brewery on Belvedere Road.

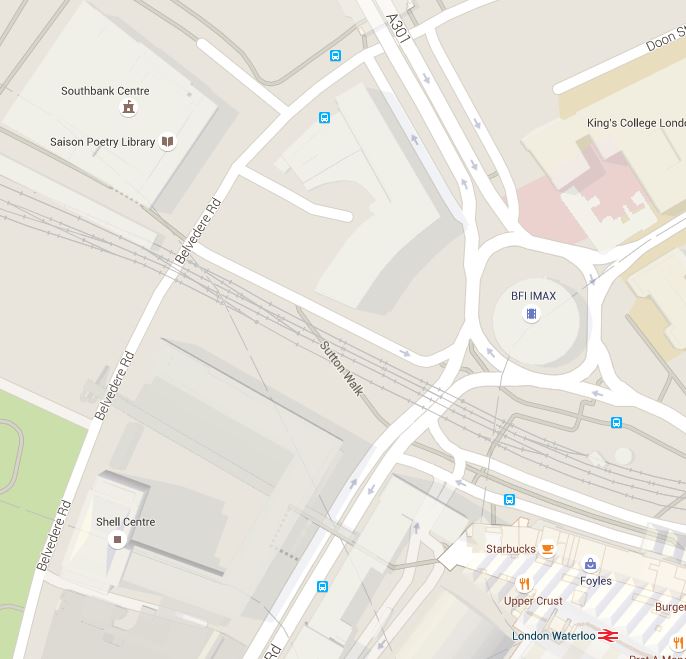

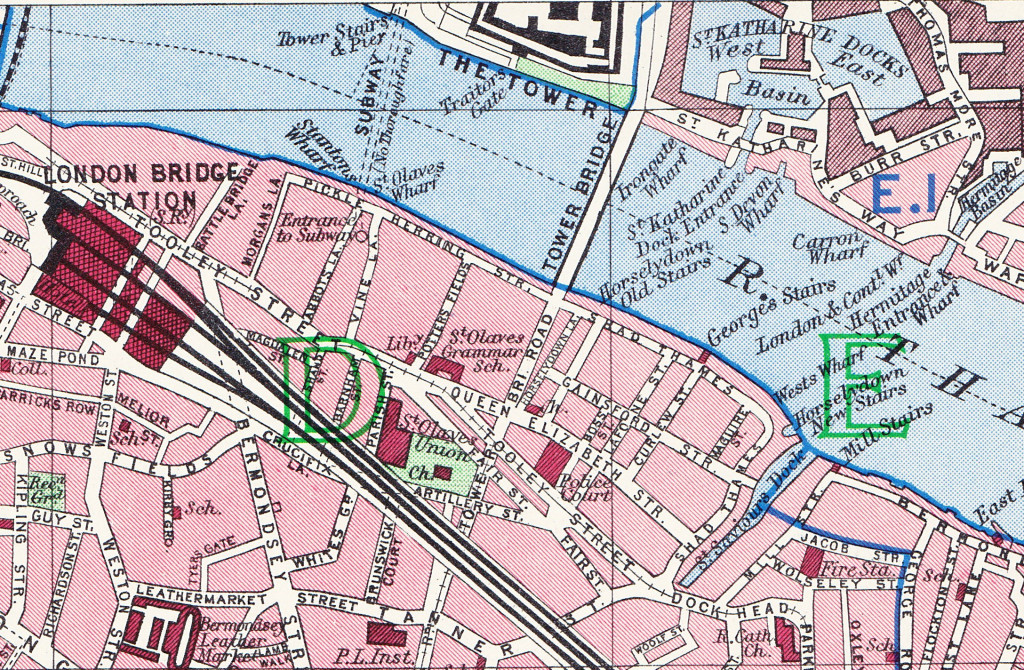

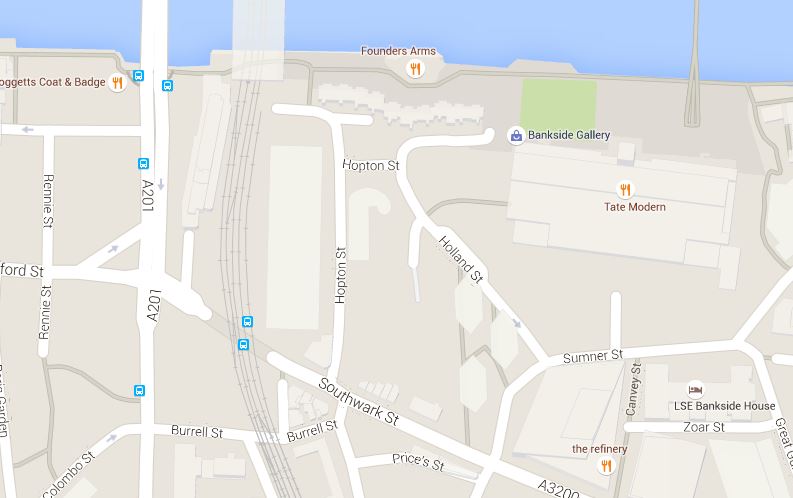

This is the location of Sutton Walk in 2015, in the centre of the map, the short stretch under the rail tracks:

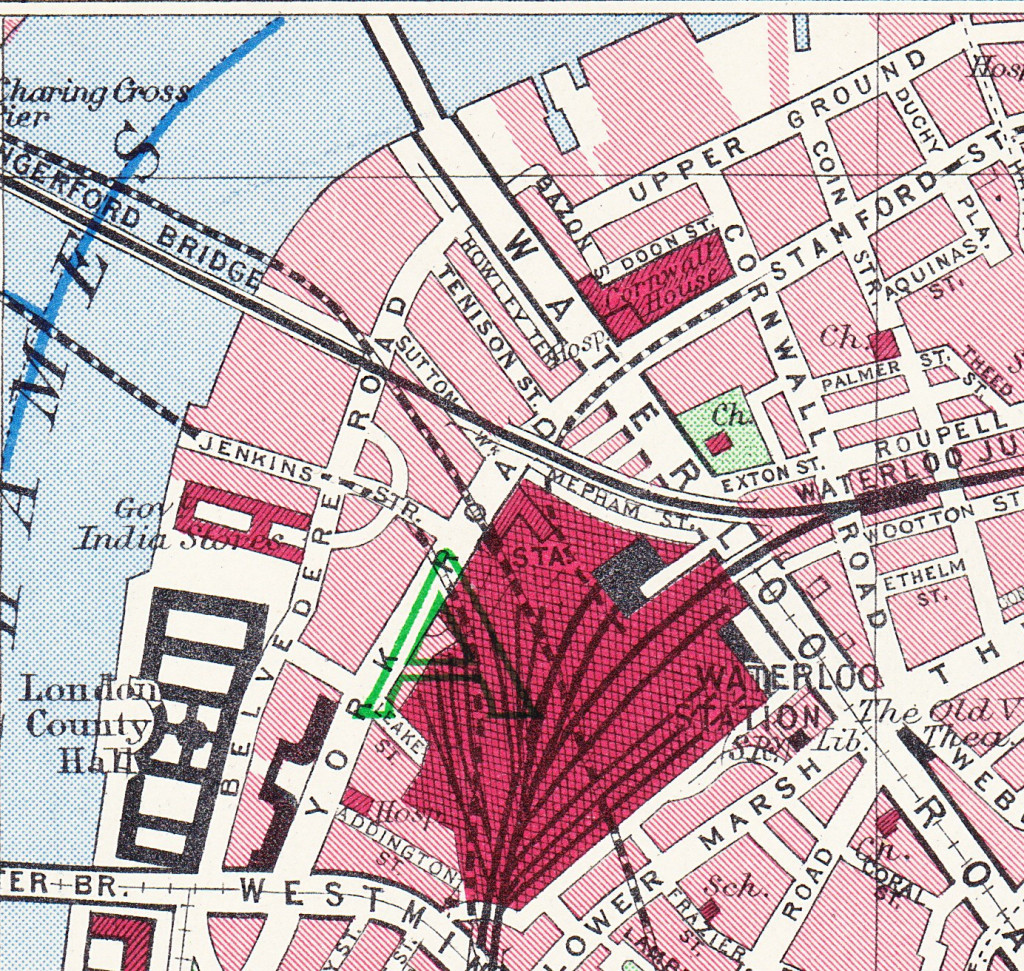

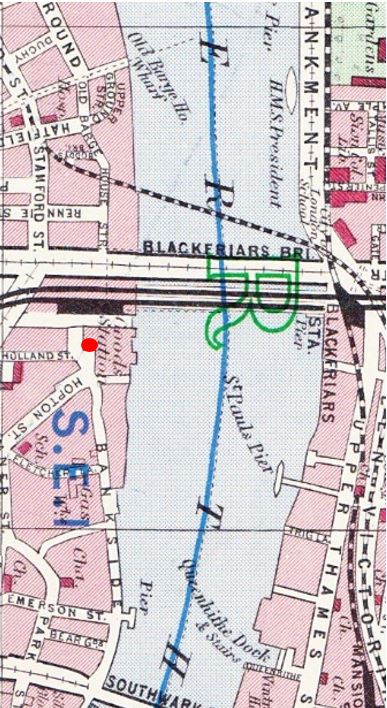

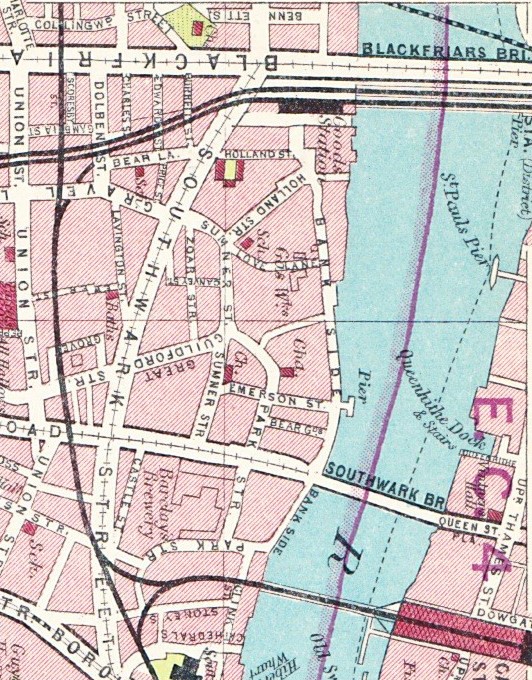

Before the post war development of the area for the Festival of Britain, the 1940 Bartholomew’s map showed the original Sutton Walk:

Before the demolition of the original buildings along Belvedere Road, my father took some photos in 1947 from the junction of Sutton Walk with Belvedere Road. These show part of the old Lion Brewery that are not often seen. There are many photos from the river (including some my father took here), but in this article I want to show the other side of the brewery.

In the first photo, we are standing in the original Sutton Walk. The road running left to right is Belvedere Road. Straight ahead is the archway leading into what was the Lion Brewery. The word “Brewery” remains on the block at the top of the arch, however the stone Lion that originally sat on top of the arch has already been removed, leaving only the stubs of metal rods that would have held the Lion to the arch.

Framed within the archway is Shell-Mex House on the north bank of the river. Originally on the right of the arch was a building of identical design to the building remaining on the left, and the main brewery buildings would have been visible through the arch. It must have been an impressive sight when the brewery was in full production.

Framed within the archway is Shell-Mex House on the north bank of the river. Originally on the right of the arch was a building of identical design to the building remaining on the left, and the main brewery buildings would have been visible through the arch. It must have been an impressive sight when the brewery was in full production.

One can only imagine the number of barrels of beer that have come through that archway.

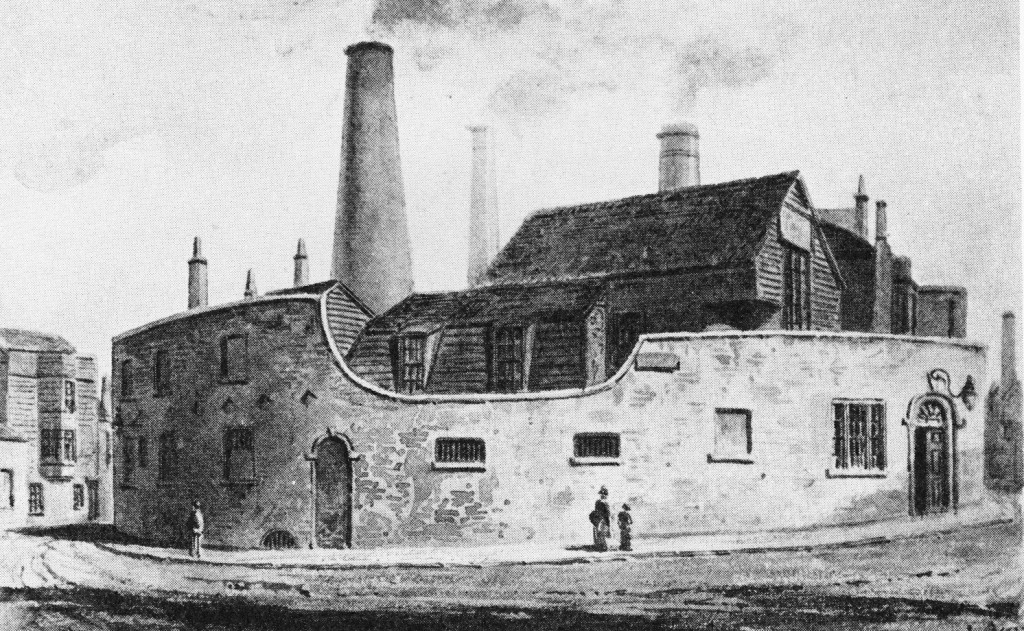

The brewery was built between 1836 and 1837 on the site of a Water Works that supplied water to the local area using water taken directly from the river. Prior to the water works, a house called Belvedere (the origin of the road name) occupied the site. This became a tavern in 1781 and along with the gardens, was opened to the public following the tradition of “pleasure gardens” being opened along the south bank of the river.

The brewery building was seriously damaged by fire in 1931, after which it was used for a brief period as a storage place for waste paper.

This whole area was demolished in the late 1940s ready for the construction of the Royal Festival Hall and many of the streets were either lost or considerably changed. Although Sutton Walk does not now extend down to Belvedere Road it is still easy to find the location of my father’s photos by extending the line of the remaining pedestrian stretch under the railway.

The same view today from roughly the same position:

The Royal Festival Hall now fully occupies the site of the Lion Brewery between Belvedere Road and the Thames.

The Royal Festival Hall now fully occupies the site of the Lion Brewery between Belvedere Road and the Thames.

The next photo is from the end of Sutton Walk and looking to the right along a short stretch of Belvedere Road. Behind the building we can see the top of the Shot Tower. The top of the tower still in the original state prior to the modification for the Festival of Britain. The lettering on the wooden gate in the centre of the photo spells out the name of the London Waste Paper Company Ltd. After the brewery closed, the site was used for storage of waste paper by this company.

The same view in 2015 looking at the edge of the Royal Festival Hall and towards the Hayward Gallery (hidden behind the tree):

The same view in 2015 looking at the edge of the Royal Festival Hall and towards the Hayward Gallery (hidden behind the tree):

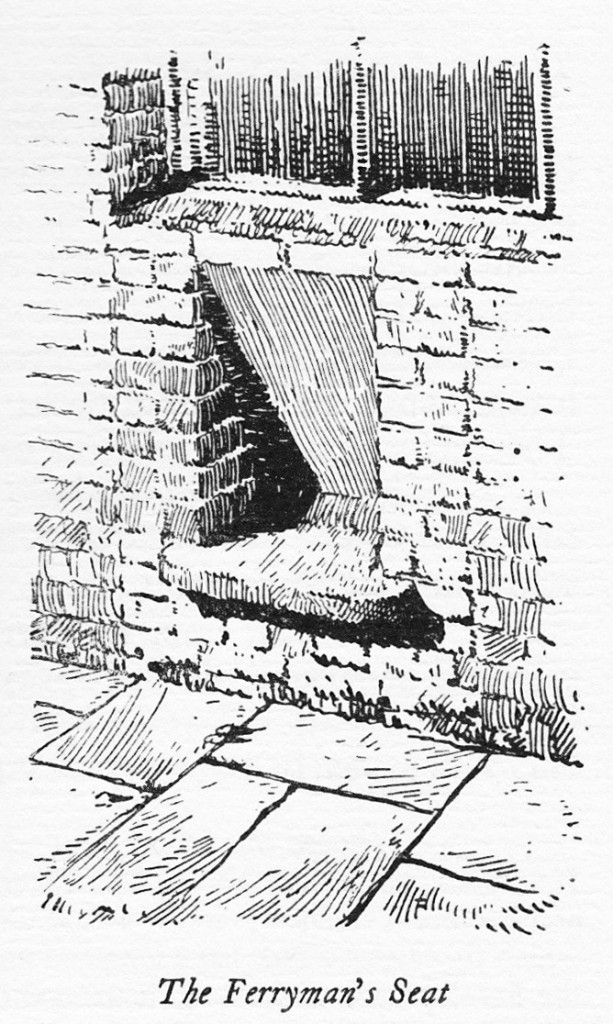

Now we can cross over Belvedere Road and look back at the junction with Sutton Walk and we can see another part of the brewery with the same style of entrance arch, but still retaining the lion. This part of the brewery site contained warehousing and the stables.

Now we can cross over Belvedere Road and look back at the junction with Sutton Walk and we can see another part of the brewery with the same style of entrance arch, but still retaining the lion. This part of the brewery site contained warehousing and the stables.

Also in the above photo, there is a pub on the right. There were several pubs along Belvedere Road as before the war, this was a very busy light industrial and residential area. It looks still occupied, but when the photo was taken in 1947 this area had mainly been cleared and the pub would soon be demolished.

Also in the above photo, there is a pub on the right. There were several pubs along Belvedere Road as before the war, this was a very busy light industrial and residential area. It looks still occupied, but when the photo was taken in 1947 this area had mainly been cleared and the pub would soon be demolished.

And the same view in 2015. The building is the old Shell Centre Downstream building which is now “The Whitehouse”, one of the many office to luxury apartment conversions that now seem the norm across so much of central London.

From extending the remaining stretch of Sutton Walk down to Belvedere Road, the lamp posts on the right in the two photos seem to be in exactly the same position.

This is all that is left of Sutton Walk today, the short pedestrian stretch under the railway. The road running left to right is Concert Hall Approach, a new road (if you call more than 50 years old, a new road !!), built as part of the redevelopment of the area.

This is all that is left of Sutton Walk today, the short pedestrian stretch under the railway. The road running left to right is Concert Hall Approach, a new road (if you call more than 50 years old, a new road !!), built as part of the redevelopment of the area.

Although Belvedere Road was named after a house on the site of the Lion Brewery, a number of other roads in this area were named after Archbishops of Canterbury (no doubt due to Lambeth Palace, the London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury being not that much further along the Thames).

Although Belvedere Road was named after a house on the site of the Lion Brewery, a number of other roads in this area were named after Archbishops of Canterbury (no doubt due to Lambeth Palace, the London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury being not that much further along the Thames).

Sutton Walk was named after Charles Manners-Sutton (Archbishop between 1805 and 1828).

The nearby Tenison Street, (see the 1940 map, next street up towards Waterloo Bridge, lost during the construction of the Shell buildings) was named after Thomas Tenison (Archbishop from 1694 to 1715).

Although the street is not named in either the 2015 or 1940 maps, the street that runs from the corner of County Hall towards Leake Street is Chicheley Street. This street is still there and is named after Henry Chichele (Archbishop from 1414 to 1443).

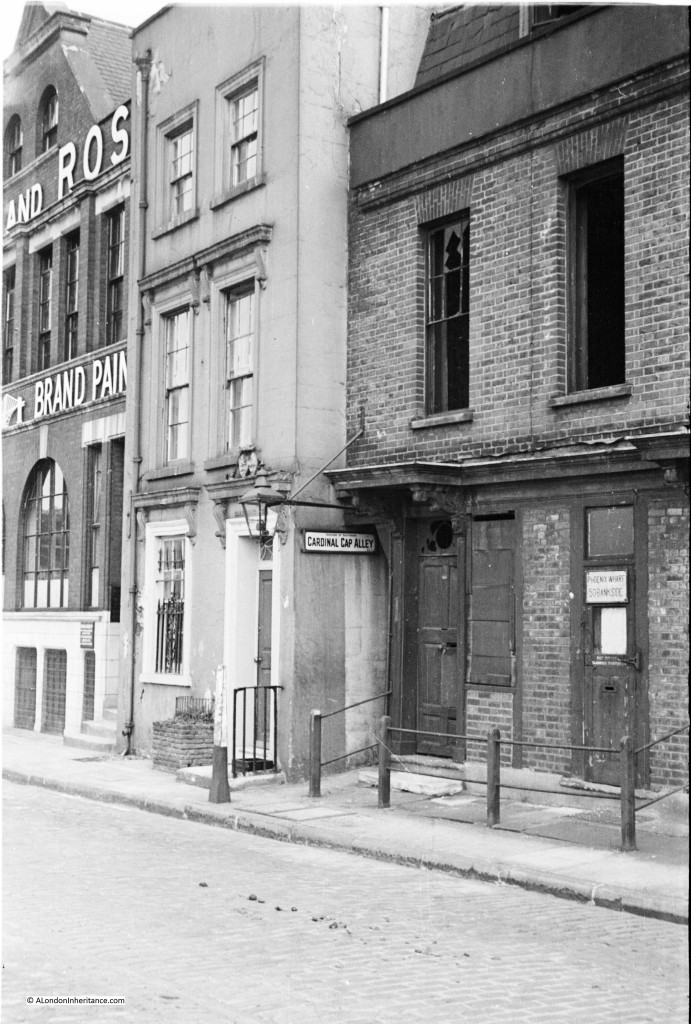

Returning to Belvedere Road, we can walk to the right, eastwards towards Waterloo Bridge. This was the view in 1947 with the approach to Waterloo Bridge crossing over Belvedere Road:

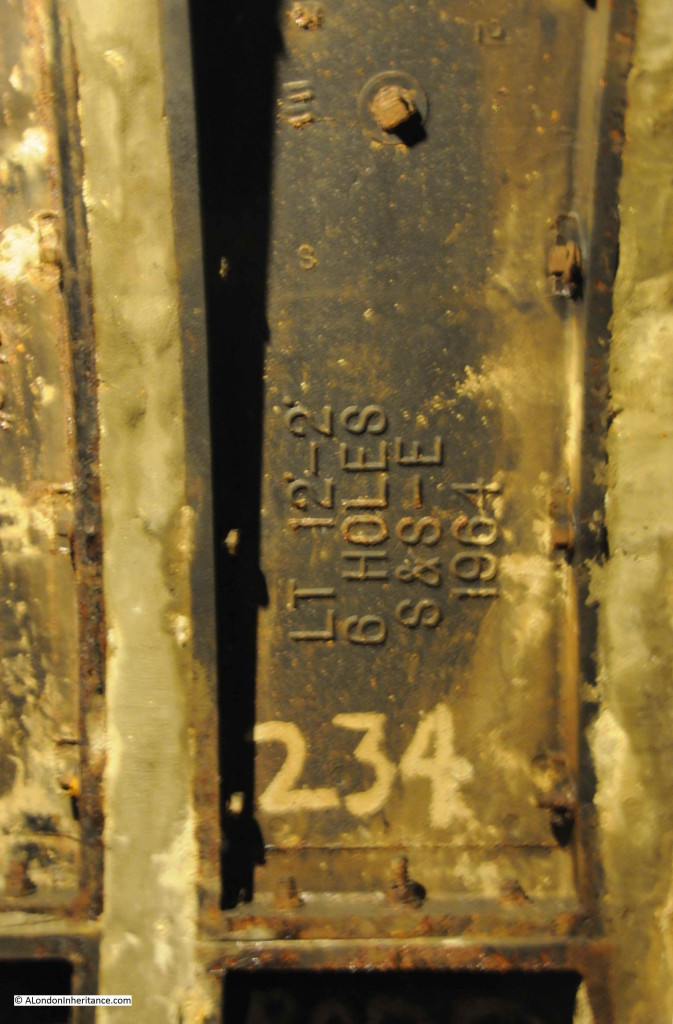

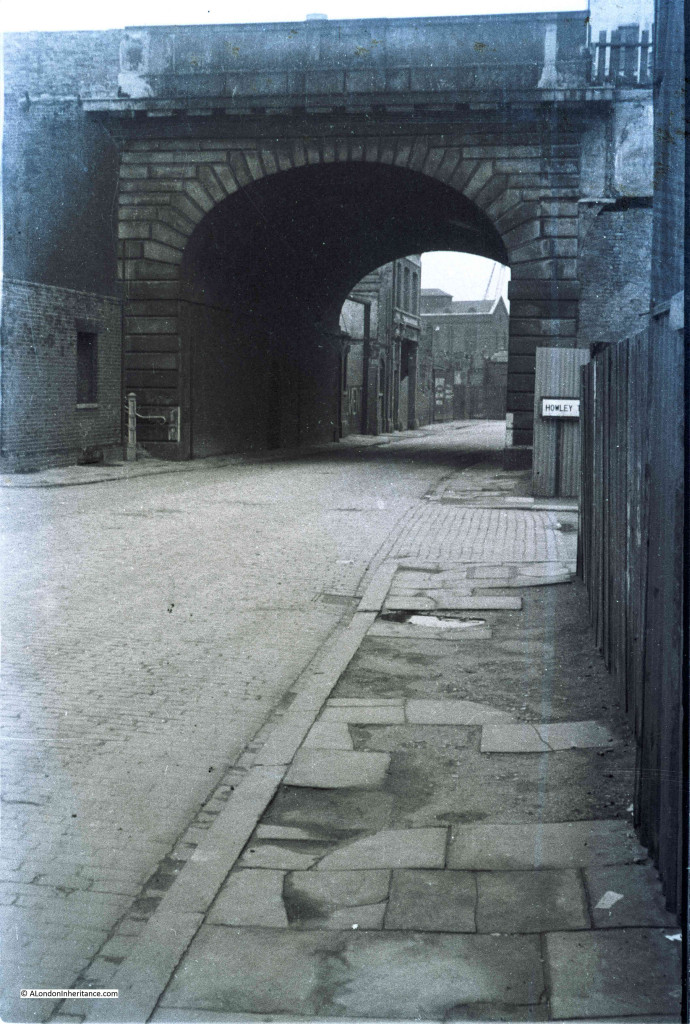

Although the current Waterloo Bridge was built in the early 1940s and opened in 1945, it still used the original approach road and the arches over the roads on the southbank. To confirm that this is indeed the location, look to the right of the above photo and part of a street sign can be seen.

Although the current Waterloo Bridge was built in the early 1940s and opened in 1945, it still used the original approach road and the arches over the roads on the southbank. To confirm that this is indeed the location, look to the right of the above photo and part of a street sign can be seen.

This is Howley Terrace and using the 1940 street map, Howley Terrace can be seen running parallel to the Waterloo Road as it runs up to the bridge (and continuing the street name theme, Howley Terrace was named after William Howley, Archbishop from 1828 to 1848 – this also provides a good estimation of when these streets were named, probably around1848 as William Howley is the last Archbishop to have a street named after him in this area).

The naming of streets after Archbishops extended beyond the area between York Road and Belvedere Road. The street in front of Waterloo Station, Mepham Street (seen in the above 1940 map and still in existence) was named after Simon Mepeham, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1329 to 1333). The history of the church appears to be written across this area of Lambeth.

The view is very different now. The new approach road to Waterloo Bridge, built as part of the redevelopment of the area provides a very different crossing of Belvedere Road. There is still a road turning off to the right. This is now a slip road down from the roundabout at the end of the road to Waterloo Bridge, down to Belvedere Road. Unlike Sutton Walk, the slip road does not appear to have any name, therefore the name Howley Terrace looks to be consigned to history.

I find the Southbank fascinating. It is one of the areas in London that has undergone such significant post war development that there are very few traces of what was there before. The railway running up to Hungerford Bridge is the only remaining structure that has survived, but it is good that some of the streets can still be found, even though, as with Sutton Walk, it is now a shadow of its former state.