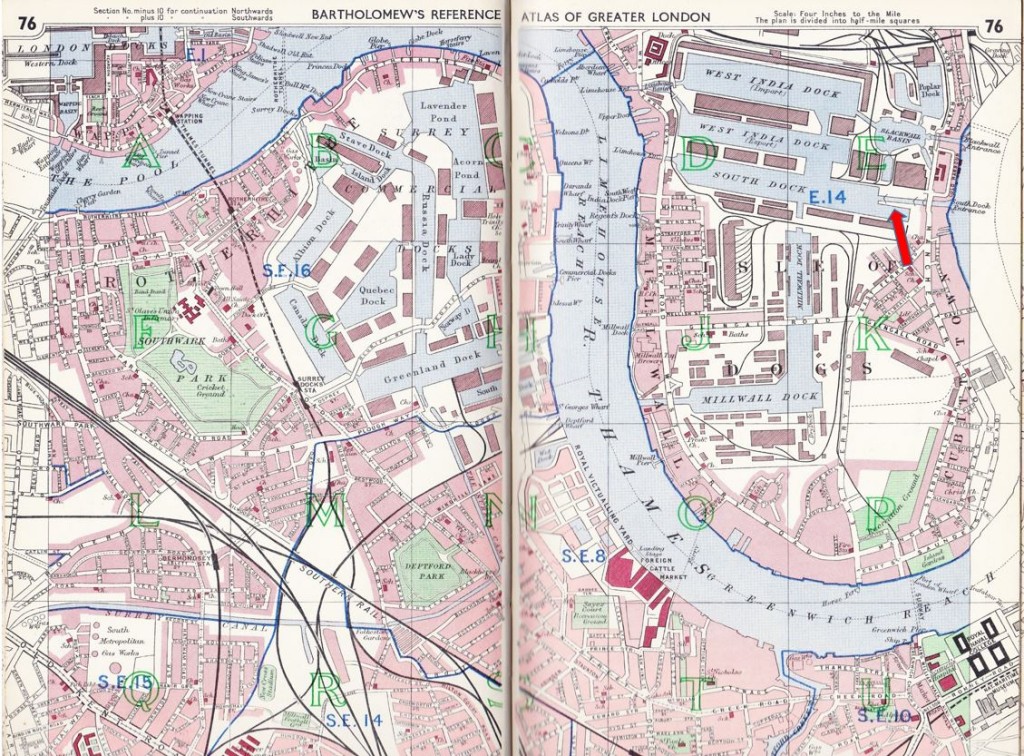

I have to blame a busy week at work for a different post this week to the one I had planned as I had hoped to visit a couple of locations for some research, so for this week’s post I would like to take you on a walk along the Greenwich Peninsula. It is rather brief, but does cover a fascinating part of London and one that is to see some significant change over the next few years.

London is changing so rapidly that it is difficult to photograph places and buildings before they change or disappear and the subject of this week’s post is an area I wish I had photographed before, I have walked the area but did not photograph, so this is very much a catch-up.

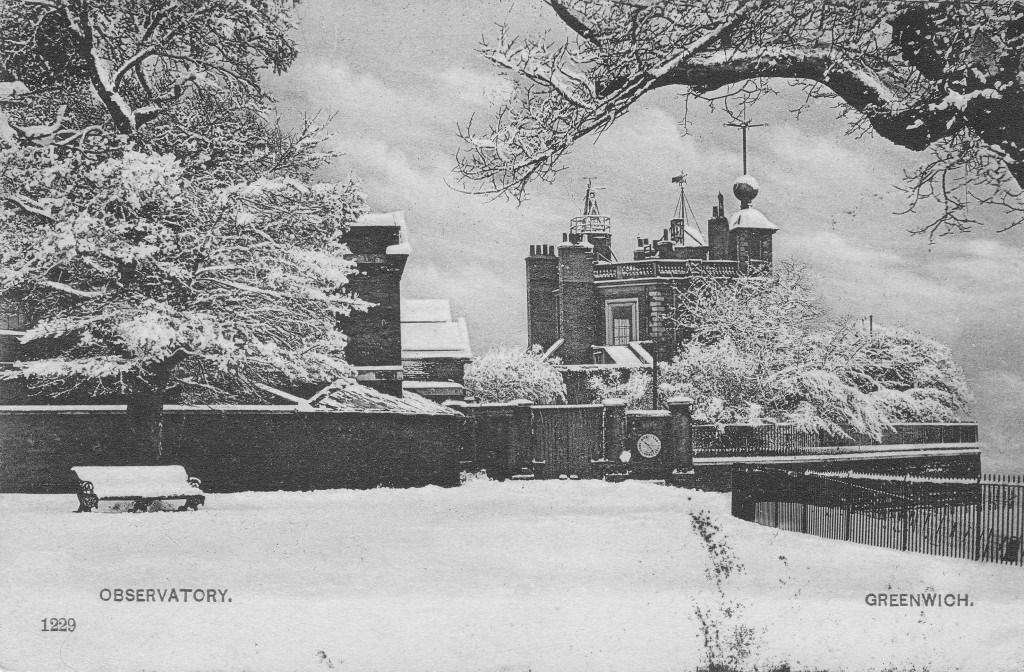

Greenwich is mainly known for the Royal Observatory, the National Maritime Museum, Cutty Sark etc. however step a short distance away from these places and there are the remains of an industrial landscape that will soon be covered in the ubiquitous apartment buildings that can be seen across London, all basically to the same design and of the same materials.

As well as the apartment buildings, this area is also planned to be the site of a cruise ship terminal in the next few years, providing visitors with access to both Greenwich and central London.

The photos below come from a couple of last year’s walks from Greenwich to the O2 Dome. The area has a fascinating industrial history and for a very well researched book about the area I can highly recommend the book Innovation, Enterprise and Change on the Greenwich Peninsula by Mary Mills.

Starting from the Greenwich Pier, the view along the river gives an indication of what is to come with cranes in the distance towering above new construction work.

Walking along the river path having passed the buildings of the Old Royal Naval College and along a side road, is the Trinity Hospital and Greenwich Power Station.

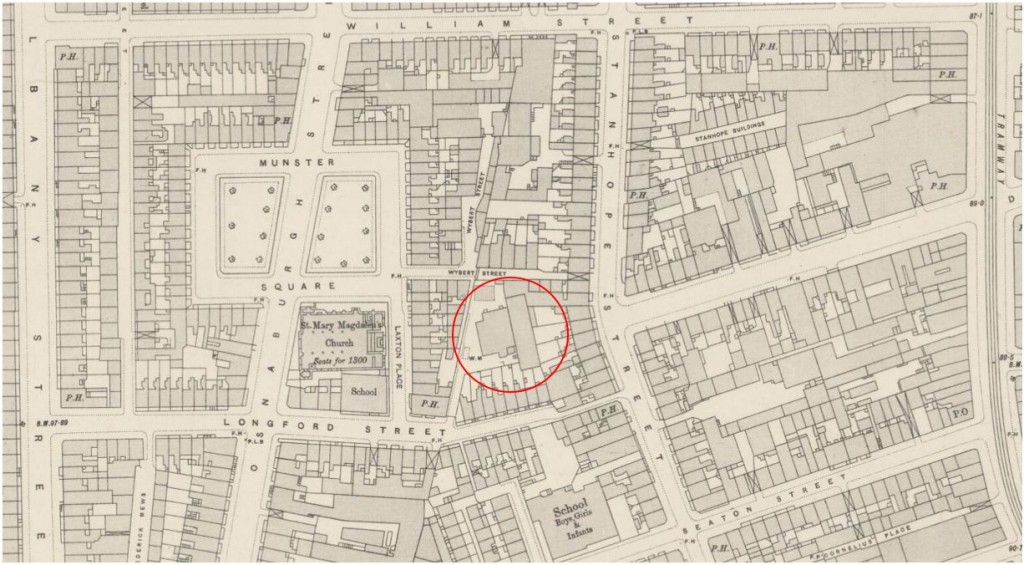

The Almshouses of Trinity Hospital have been on the site since the 17th century, but the current buildings are from the early 19th century. The adjacent power station was built at the start of the 20th century to power the London tram and underground network, however since the transfer of the power supply for the underground to the National Grid, the Greenwich Power Station retains a role as a backup generator.

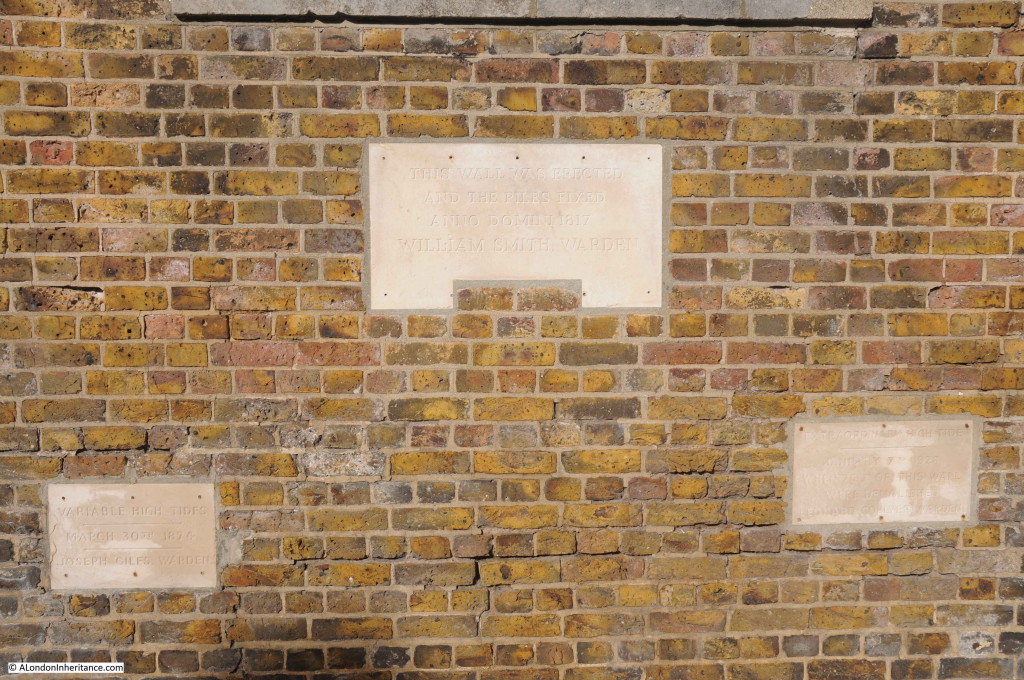

The river wall in front of the Almshouses records past levels of flooding.

The lower left plaque records the height of the tide on the 30th March 1874. The plaque on the right records “an extraordinary high tide” on January 7th 1928 when “75ft of this wall were demolished”.

The plaque at the top records that the wall was “erected and the piles fixed” in the year 1817.

Walk along a bit further and it is possible to look back to the river wall in front of the Almshouses and see the remains of the original steps that led up from the river. A reminder of when the majority of travel to sites along the river would have been on the river.

The original coal supplies for the power station came by river and the jetty remains, now unused as the limited amount of oil and gas needed for the power station in a standby role is delivered by road.

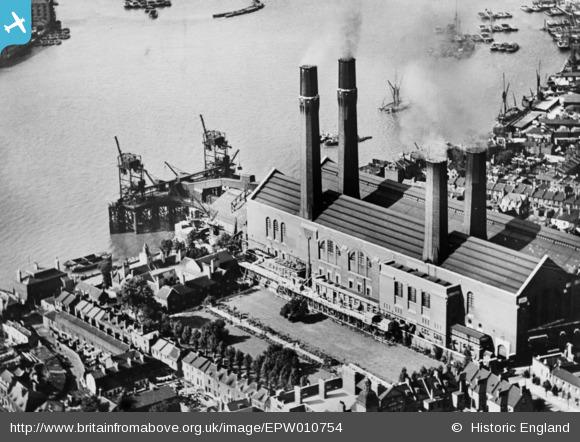

The Britain From Above website has an excellent aerial photo of the power station in full operation in 1924. The almshouses can be seen to the left with their gardens running back in parallel to the power station. This is photo reference EPW010754

Walk past the power station and the Cutty Sark pub (a good stop before setting off towards the Dome) and the building marked as the Harbour Masters Office is the last building before we come to what was the old industrial area and is now the subject of much redevelopment.

Walk up a short ramp and this is the view. Whilst there is an urgent need for lots more housing in London, why do all apartment buildings have to look identical and obliterate any local character.

There are the remains of a number of artworks along this stretch of the Thames. Here a line of clocks tied to fencing.

Some parts of the walk are between fenced off industrial areas waiting for development. Indeed walking along the path you do get the feeling that the area is just waiting – the industry has gone, the new development has not yet started.

Where the pathway runs along the river there are a surprising number of trees. Here an apple tree, intriguing to think that this could have grown from the seeds in an apple core thrown down by a long departed worked, or possibly washed down the Thames.

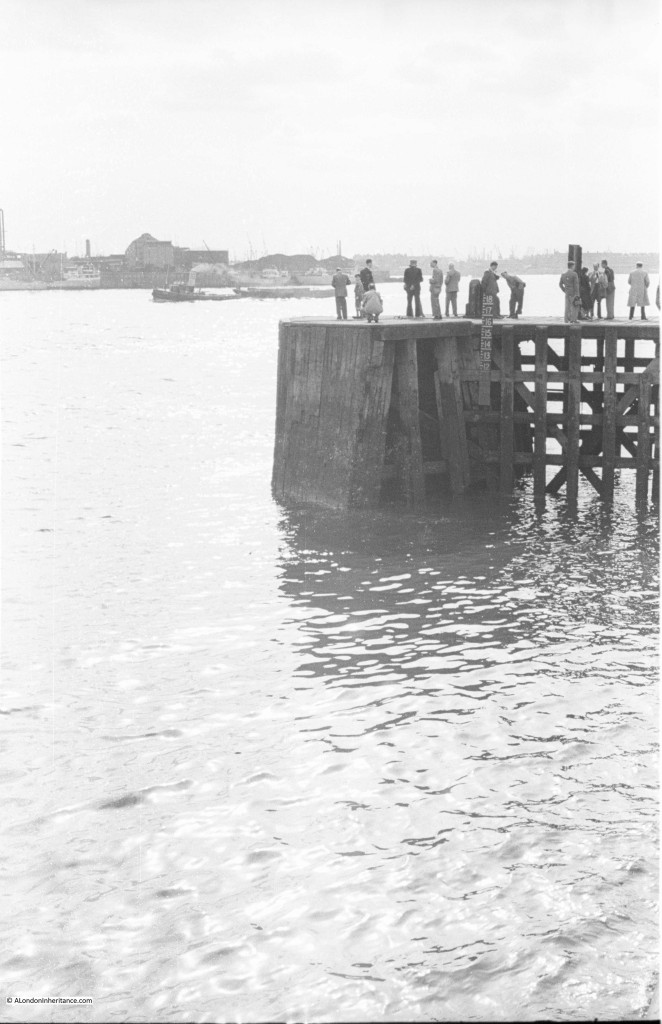

One of the main industries along this stretch of the river was the manufacture of submarine communication cables which took place at Enderby Wharf and it is here that we can see the remains of some of this activity.

Here was manufactured the first cable to cross the Atlantic and up until the mid 1970s much of the world’s subsea communication cables had been manufactured here. The web site covering the history of the Atlantic Cable and Undersea Communications has a detailed history of Enderby Wharf.

The two structures that can still be seen are part of the mechanism for transferring cable from the factory on the right to cable ships moored in the Thames to the left. Cable would be run across the walkway to the top of the tower on the right then to the round hold-back mechanism on the left then onto the ship.

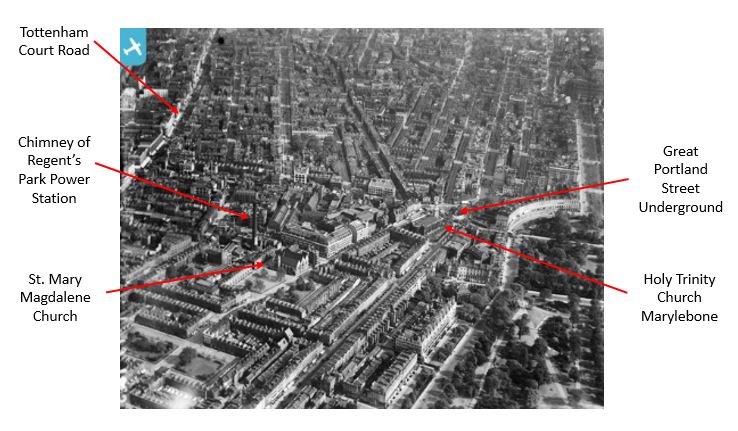

Again, the Britain from Above web site has a photo of the Enderby Wharf site which is in the middle of the photo. This is photo reference EAW002289

The following photo is why I wish I had taken photos along this stretch of the Thames some years ago. Hoardings now block of the factory site, but only the original Enderby House remains. This is a listed building, built around 1830, but looks to be in a process of slow decay. The Atlantic Cable and Undersea Communications website has lots of detail on Enderby House and how the building has decayed.

All I can do now is climb on the river wall and try to look over the hoardings.

Looking onto Enderby’s Wharf. Cable being run onto ships would have crossed directly above on its route from the factory.

How Barratt Homes plan to develop Enderby Wharf can be found here.

Look into the river and a set of steps running down into the Thames can be seen. These are the Enderby Wharf Ferry Steps. Whilst steps into the river have been here for many years, these steps are recent, having been installed in 2001.

The plaque at the top of the steps.

The plaque records that:

These steps originally gave access to the row boat and ferry man that ferried crew members between the shore and the cable ships anchored off-shore in the deeper central channel of the river.

They also pass alongside the Bendish Sluice, one of the four sluices established in the 17th century to draw off the water from the natural marshlands that constitute Greenwich Peninsula.

From the mid 1800’s until 1975 telegraph and latterly telephone cables have been manufactured at Enderby Wharf and were stored in vast tanks at the works which Alcatel now operate. These cables were loaded into the holds of ships while they lay anchored in the river. Cable produced at this site were used to establish the first links between England and France; the last cable made on the Greenwich site linked Venezuela with Spain.

Looking down the Enderby Wharf Ferry Steps:

Another view of the cable transfer machinery.

It is in this area that the cruise terminal is planned to be built. The London City Cruise Port will be at Enderby Wharf and will allow mid-sized cruise ships to moor at a site with easy access to Greenwich and central London. I only hope that Enderby House, the original cable transfer machinery and the Enderby Wharf Steps are retained and protected.

It is in this area that the cruise terminal is planned to be built. The London City Cruise Port will be at Enderby Wharf and will allow mid-sized cruise ships to moor at a site with easy access to Greenwich and central London. I only hope that Enderby House, the original cable transfer machinery and the Enderby Wharf Steps are retained and protected.

A short distance past Enderby Wharf is Tunnel Wharf.

And the hoardings continue to fence off the areas waiting for redevelopment. This is Morden Wharf.

Parts of the path seem to have a distinctly rural quality with trees lining the slopping river bank down into the Thames.

But the remains of old industrial areas soon return. London will soon be losing the majority of the old gas holders that were once major landmarks across the city. I do not know if this large gas holder on the Greenwich Peninsula is protected, I suspect not.

Walking past the area where some of the river’s shipping is maintained in a row of dry docks.

Looking across from the river path to the Dome, with the grade 2 listed entrance to the Blackwall Tunnel.

The final stretch of the river walk before reaching the new developments around the O2 also have an air of waiting for a different use.

A large site is used for the storage and processing of aggregates that arrive by barge along the river.

And then we reach the area leading up to the Dome consisting of a golf driving range:

And another building site and behind, a building that I cannot understand how an architect thought would be a good design for this location.

The Greenwich Peninsula has not attracted the same attention as much of the recent development in central London, however it is an area that will be changing dramatically over the next few years as stretches of almost identical glass and steel buildings run further along the river.

Now where to photograph next in a continually changing city?