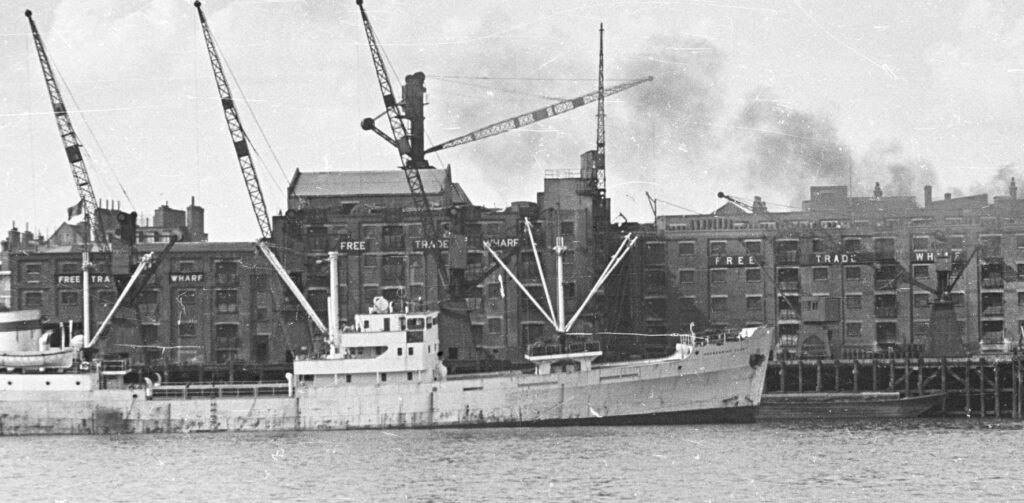

Back in 2017, I started a series of blog posts about an article in the Architects’ Journal on the 19th of January 1972. This issue had a lengthy, special feature titled “New Deal For East London”. The feature reported on the challenges facing the whole area to the east of London, which by the 1970s had been in continuous decline since the end of the last war, along with the future impact of some of the very early plans for major developments across the whole area to the east of London.

The article identifies a range of these challenges and developments, including:

- The impact on the London Docks of the large cargo ships now coming into service

- The lack of any strategic planning for the area and the speculative building work taking place, mainly along the edge of the Thames

- The location of a possible Thames Barrage

- The impact of the proposed new London airport off the coast of Essex at Foulness

- The need to maintain a mixed community and not to destroy the established communities across the area

A key focus of the article is a concern that should there be comprehensive development of the area in the coming years, then a range of pre-1800 buildings should be preserved. The article included a map that identified 85 locations where there are either individual or groups of buildings that should be preserved. The area includes parts of south London, although still to the east of the central city area, therefore considered as being east London.

The map was split across two pages and the locations were divided into five categories, identified by their historical origins:

A – Areas that were developed as overflow from the City of London

B – Linear development along Thames and Lea due to riverside trades

C – Medieval village centres

D – Early 19th century ribbon developments

E – Medieval village centres along southern river bank and around London Bridge

Between 2017 and 2019, I went in search of a large number of locations listed in the article, and followed up with posts documenting what had survived, and also where there had been changes, however after 2019 I did not finish working through the list of 85 locations, so today’s post is the first in a final set of posts for 2024, to finish of writing about all the 85 locations recorded as places at risk of redevelopment in the years following 1972.

The second page of the map included a list of the buildings, along with the area that is the focus of today’s post – Greenwich:

Greenwich is a bit of an outlier in the article. There is very little written about Greenwich in the article, and where many other individual buildings had their own numbered entry, the whole of Greenwich is covered by a single number, 82 in the map of “locations, grouping and number of buildings that should be considered for preservation if comprehensive redevelopment of East London were undertaken”.

Of the five categories of location in the article, Greenwich is identified as “E – Medieval village centres along southern river bank” and the map highlighted pre-1800 buildings in black:

In the first series of articles, there were a number of comments raised about classing places south of the river as being in East London.

This was the definition used in the article, and if you ignore the traditional north or south of the river,, they are all to the east of London. They also all shared a common relationship with the working river. They were the location of docks, industry dependent on the river, people would live and work on opposite sides of the river, they had institutions that were there because of the river, people who arrived by the river would stay and live on both sides etc.

So classing these places as East London is a classification I rather like as they had much in common, and a considerable amount of their development was dependent on the river, and of being east of London where the major developments needed to support the growing trade and commercialization of the river, had space to be built.

The map for Greenwich covers a considerable area, from all the streets to the west of Greenwich Park, through the centre of Greenwich, the Royal Observatory and the old Royal Hospital and Naval College buildings, then to the east with some houses along the river, then around the power station.

Rather than have one extremely long post, I will therefore cover the Architects’ Journal map of places that should be preserved in two posts, with today’s post covering the Royal Observatory and the streets to the west, so starting at the top of the hill in Greenwich Park, where we find the:

Royal Observatory

The Royal Observatory sits at the top of the hill that rises from the land alongside the river, and through the Prime Meridian, or 0 degrees Longitude, which runs through the observatory as defined by the astronomer Sir George Biddell Airy, and recognised internationally in 1884. The Prime Meridian is one of the reasons for the Greenwich name to be known internationally.

The Royal Observatory was founded by a Royal Warrant of King Charles II in 1675, and the first building was designed by Sir Christopher Wren, and still stands at the top of the hill, and is named Flamsteed House after the Reverend John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal at Greenwich:

Whilst the Royal Observatory has hardly changed in the 50 plus years that I have been visiting Greenwich Park, the area around General Wolfe’s statue, and the hill in front, are undergoing some major changes:

The statue of General Wolfe was unveiled on the 5th of June 1930, and is by the sculptor Dr R Tait McKenzie. The statue is Grade II listed, and the Historic England listing includes the reference “Plinth much pitted by bomb fragments”, so hopefully these physical reminders of the way Greenwich was bombed will be retained.

It looks like a larger viewing area is being built in front of the statue. The view from this area must have been photographed millions of times and in summer does get very busy, so the additional space will help.

My father’s first photo of the view from here was in 1953, and my first photo dates from 1980. I wrote a post on how the view has evolved over the years in this post.

The current work is not limited to the area around the statue, the hill in front of the statue is also being changed:

This hill was a rough grassy slope running from the viewing area down to the flat grass in front of Queen’s House, however this hill is now being terraced:

The work is to restore the 17th century landscape of the park. Greenwich Park had been a hunting ground, but Charles II wanted a more formal Baroque landscape, so he engaged André Le Nôtre who had designed the gardens at the Palace of Versailles.

You can read more about the restoration work at this page on the Royal Parks website.

The following print from 1676 shows the new observatory on the hill, and to the left is a formal set of terraces running up the hill, confirming that these were a feature of the park in the 17th century:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Comparing the above print from 1676, with the photo below from 2024 shows that this view has hardly changed in 348 years. the main change to the building being the addition of the post on the left of the two central small towers with the red ball.

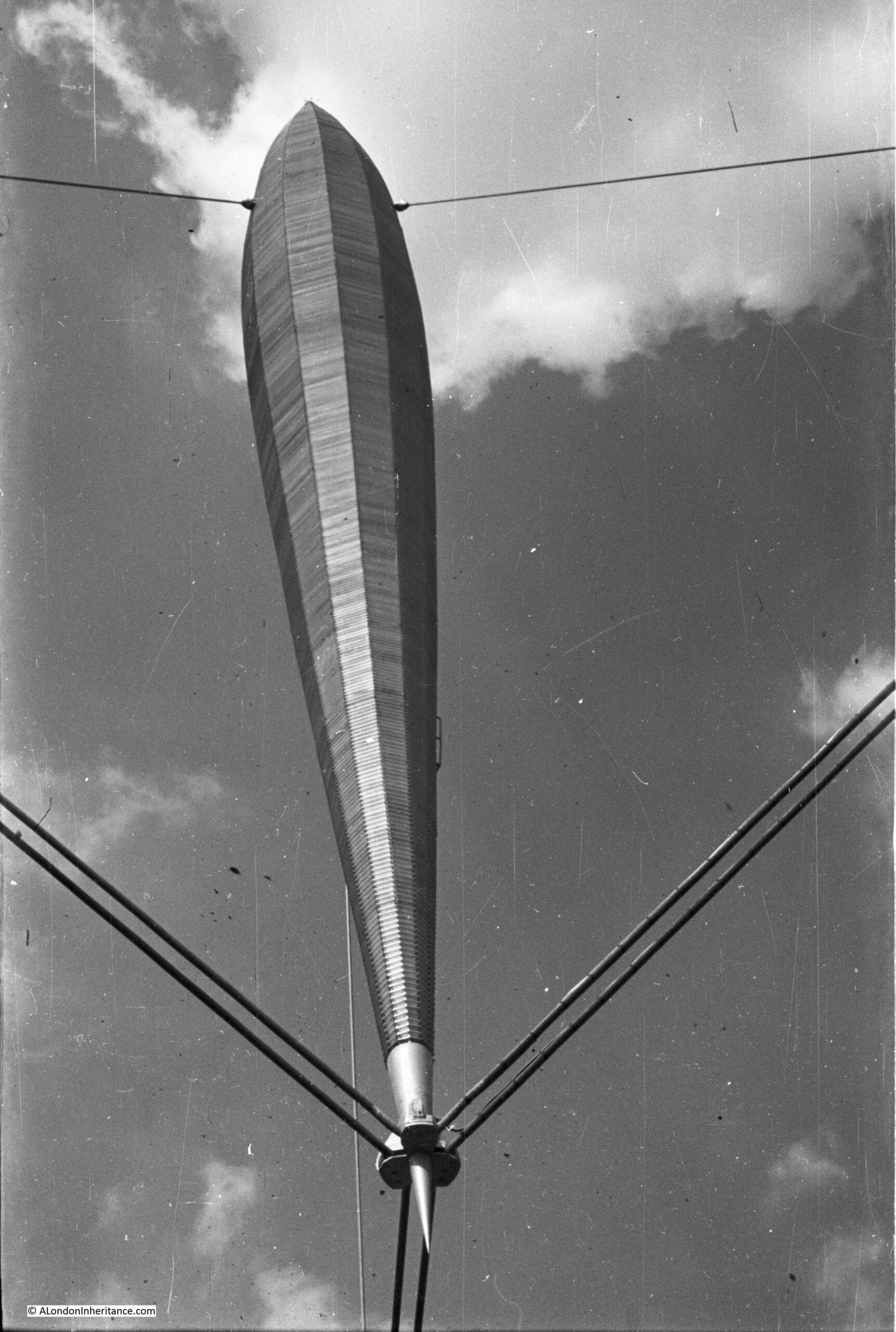

The red ball was added in 1833 and was possibly one of the world’s first public time signals, and was installed on the observatory so it was visible from the ships on the Thames, for whom time keeping, and being able to accurately set their clocks and watches was important for tides and navigation.

The ball rises to the top by 12:58 pm, each day, and then drops at 1pm as an early, visible equivalent to the “pips” which would provide an accurate time signal years later on radio transmissions.

Although you cannot look at the view from the area in front of General Wolfe, the walkway directly around the base of Flamsteed House is still open, and from here we can still look at the view.

To the east, with the Dome and Power Station:

The ever growing field of towers that now inhabit the Isle of Dogs:

Looking west to the City of London:

This path runs around the back of the oberervatory buildings and through gardens:

The Royal Observatory in Greenwich started closing in 1948 when the move to a new site in Herstmonceux, East Sussex commenced. The buildings were too dated for modern equipment, and the pollution of London was not ideal for visual astronomy.

Flamsteed House opened to the public in 1960, so I doubt the site was ever really at risk, despite being one of the black coloured buildings in the Architects’ Journal map, although being at risk is not just about the building, but also the wider environment and if large new tower blocks had been built in Greenwich and around the park, the setting of the observatory would today be very different.

To find more of the buildings highlighted in the map, I am leaving the park by one of the gates on the west, to find:

Crooms Hill

Crooms Hill runs along the western edge of the park and has a range of buildings of different architectural style and ages. It is the type of street where you are never more than a few seconds walk from a listed building.

Close to the exit from the park is this structure:

Which my father also photographed in the 1980s:

In the 1980s photo above, there is a plaque below the window on the right, which presumably provided some information about the building, however that has disappeared by 2024.

I did though find some information in the Historic England listing, as both the wall and the building are Grade II listed, and are of some age. From the listing:

“C17 high red brick wall. Gazebo of 1672, probably by Robert Hooke, perched on wall but accessible from higher ground level inside. Pyramidal tiled roof with oval wood finial. Moulded wood eaves cornice with carved modillions. Red brick North-west wall blank. South-west wall has open round arch which once contained detached Roman Doric columns and entablatures with moulded round architrave above. South-east wall has square headed opening, with shouldered, moulded brick architrave and cornice, which once contained a round inner arch. On North-east (road) front square opening with moulded brick architrave resting on band raised in centre.”

On the side of the building facing the road, there is a shield with presumably a coat of arms. The Historic England record does not mention the arms, and I can find no reference to what appears to be four scallops or shells in black and white and in this arrangement:

One of the things about a street such as Crooms Hill is the sheer diversity of architectural styles and the building materials used, as well as the changes that have been made to the buildings over the centuries.

I cannot find the following building in the Historic England list of listed buildings, but it still is of interest, with a large three storey curved end to the building, which then steps back as a relatively normal house:

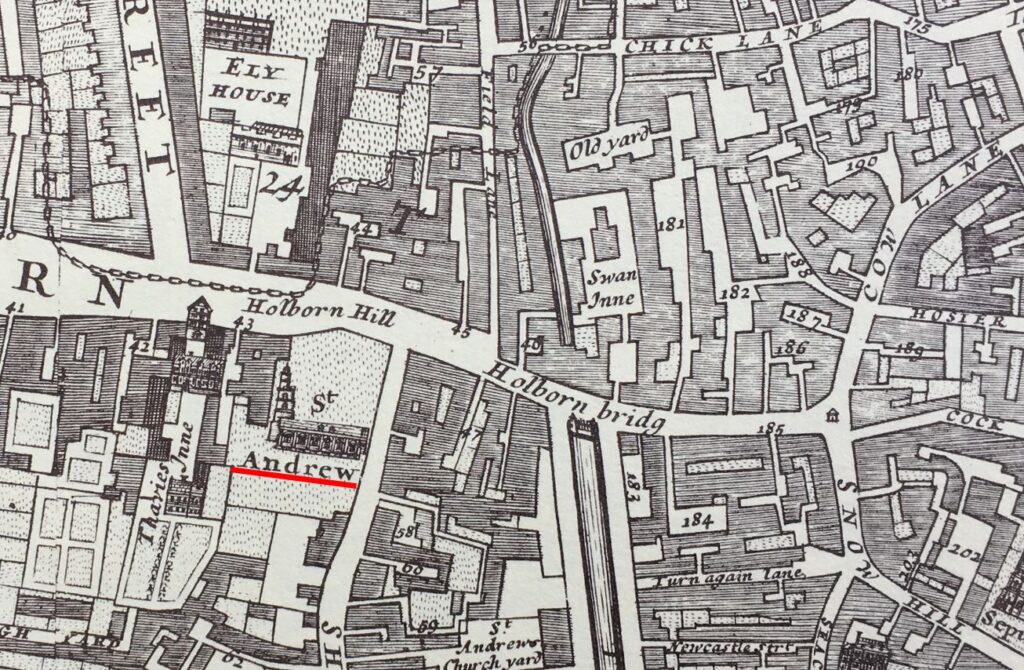

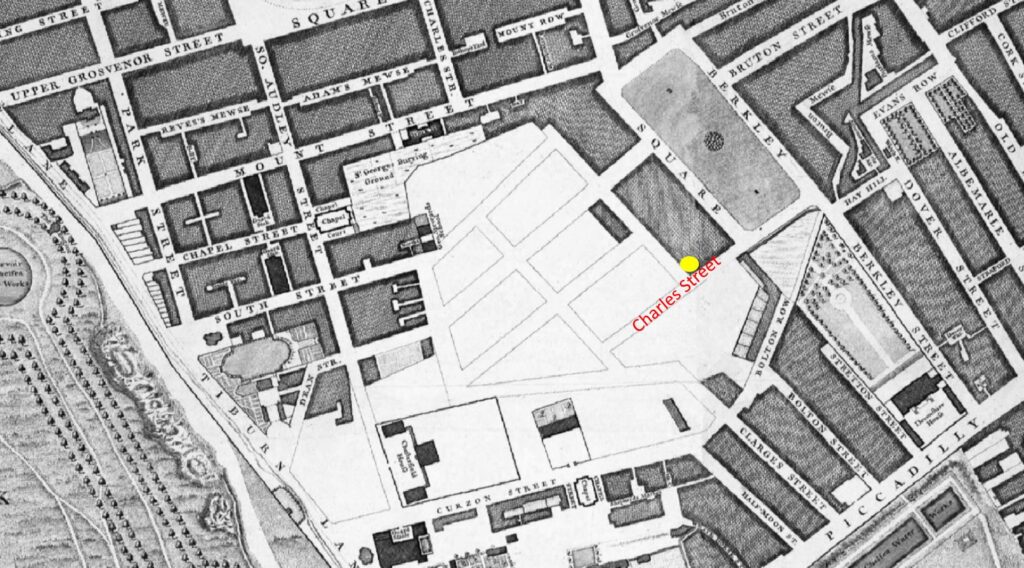

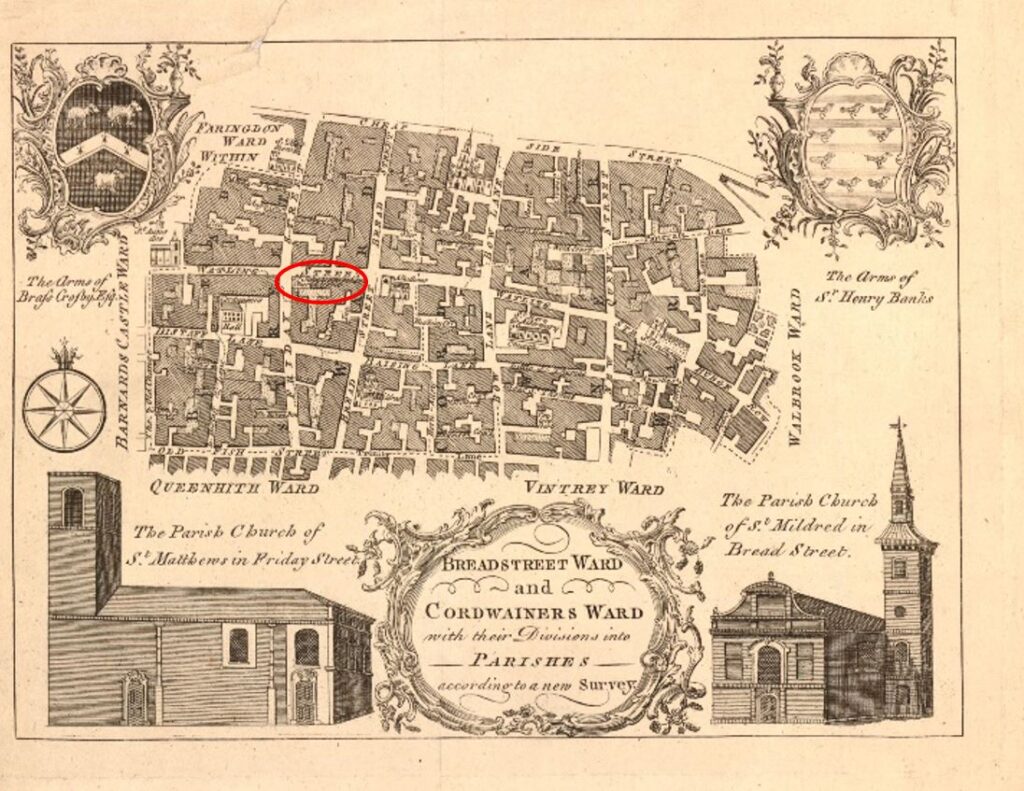

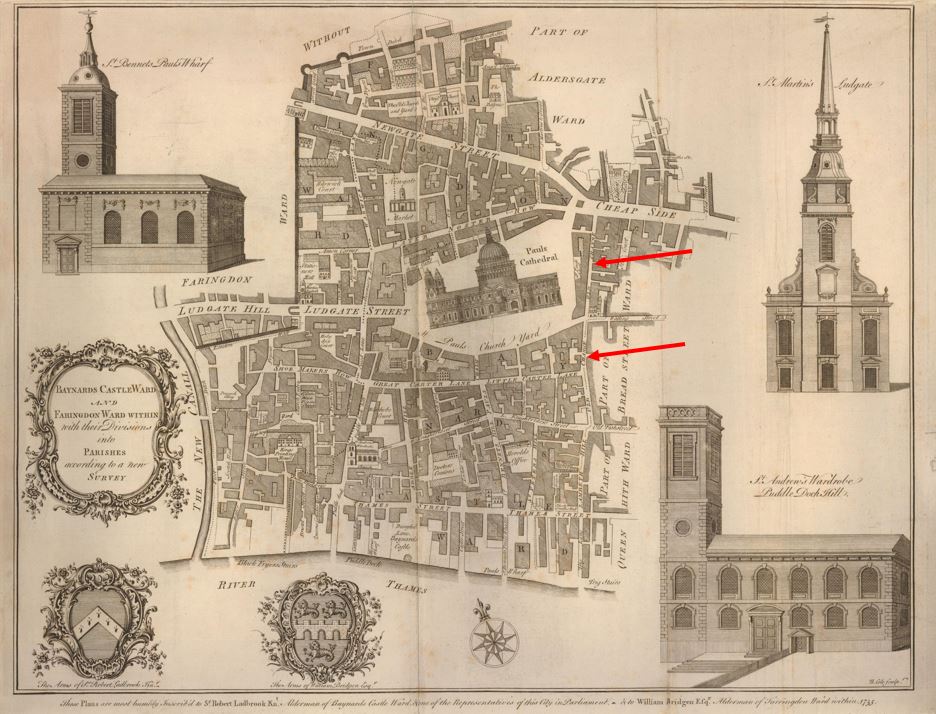

In 1746 not that much of Greenwich to the west of the park had been developed. Rocque’s map shows Crooms Hill along the western edge of the park, with a number of buildings lining the western edge of the road. These are many of the buildings that we can still see today (Crooms Hill marked with red arrow):

One of the buildings that was marked in Rocque’s map is the Presbytery. Grade II* listed and dating from 1630, but with some 18th century alterations:

The following house dates from the mid 18th century, and the house, railings, wall and gate are all Grade II listed:

Just to the right of the above photo can be seen the edge of a church. This is the Roman Catholic Church of Our Ladye Star of the Sea, which again is Grade II* listed:

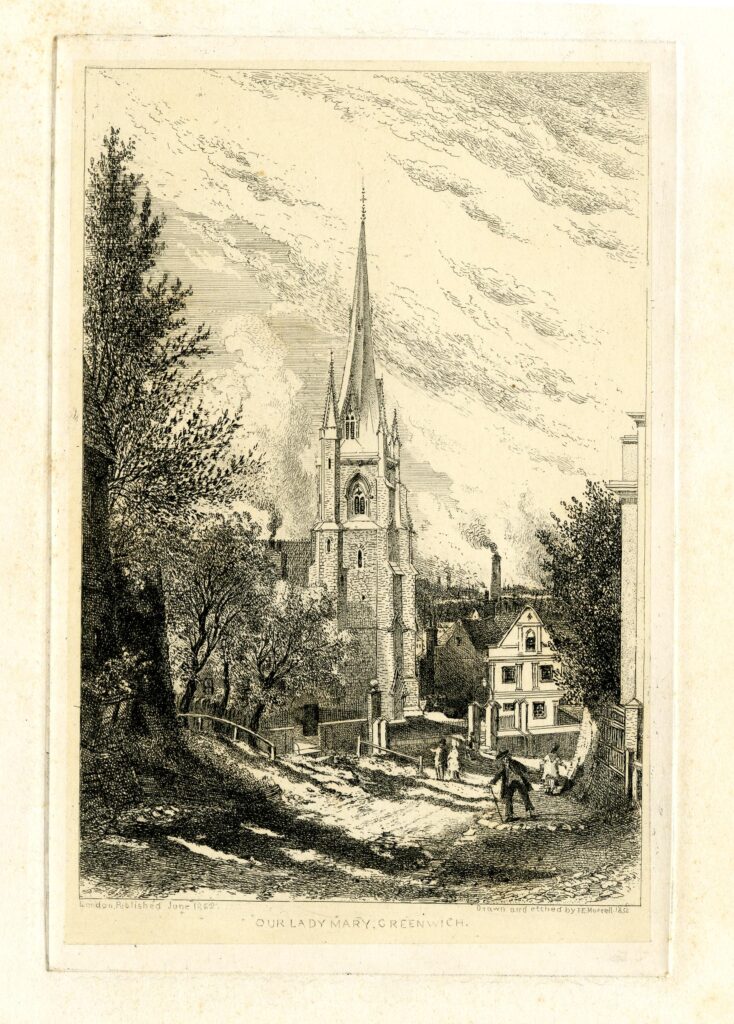

The following print from 1862 shows the church and Crooms Hill, which at the time appears to have been a relatively narrow, unpaved track. It is not that much wider today:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The church owes its origins to the maritime history of Greenwich.

In the late 18th century there were many Catholic occupants of the Royal Hospital at Greenwich. Estimates of up to 500, with numbers coming from Catholic countries such as Portugal which gives an indication of the residents of the hospital.

In 1793 a Chapel of St. Mary was built for these Catholic seamen. in the following decades, the chapel became rather inadequate, and a proper church was needed.

There is a tradition associated with the church that following the rescue of her two sons following an accident on the Thames, a Mrs. Abraham North vowed to build a church.

Fund raising covered the majority of the costs for building the church, and in recognition of the importance of the church to the maritime community, the Admiralty donated £200.

The North family donated the land for the church, and the architect William Wilkinson Wardell was employed.

Wardell was a friend of W N. Pugin, and Pugin worked on the design of the majority of fittings and furnishings within the church. Work started in 1846 and the church was completed in 1851.

Walking through the main doors into the church reveals a rather impressive interior:

The high altar was by William Wilkinson Wardell, and it was exhibited at the 1851 Great Exhibition:

Side chapel:

The Church of Our Ladye Star of the Sea is a magnificent example of mid 19th century church design and decoration, and a reminder of the connection between Greenwich, and those who worked and sailed on the Thames and the sea.

Continuing along Crooms Hill and we see plenty of one off house designs.

The tall house with the bay along the first and second floors in the following photo is Grade II listed, and indeed all the buildings in the following photo appear to be listed:

There is no single design theme running along Crooms Hill, and here is another example of the mix of styles. I suspect much of the building was speculative, made use of available plots of land, for different occupants, and variable amounts of money available to build and decorate etc. Whatever the reasons, it has resulted in a fascinating street:

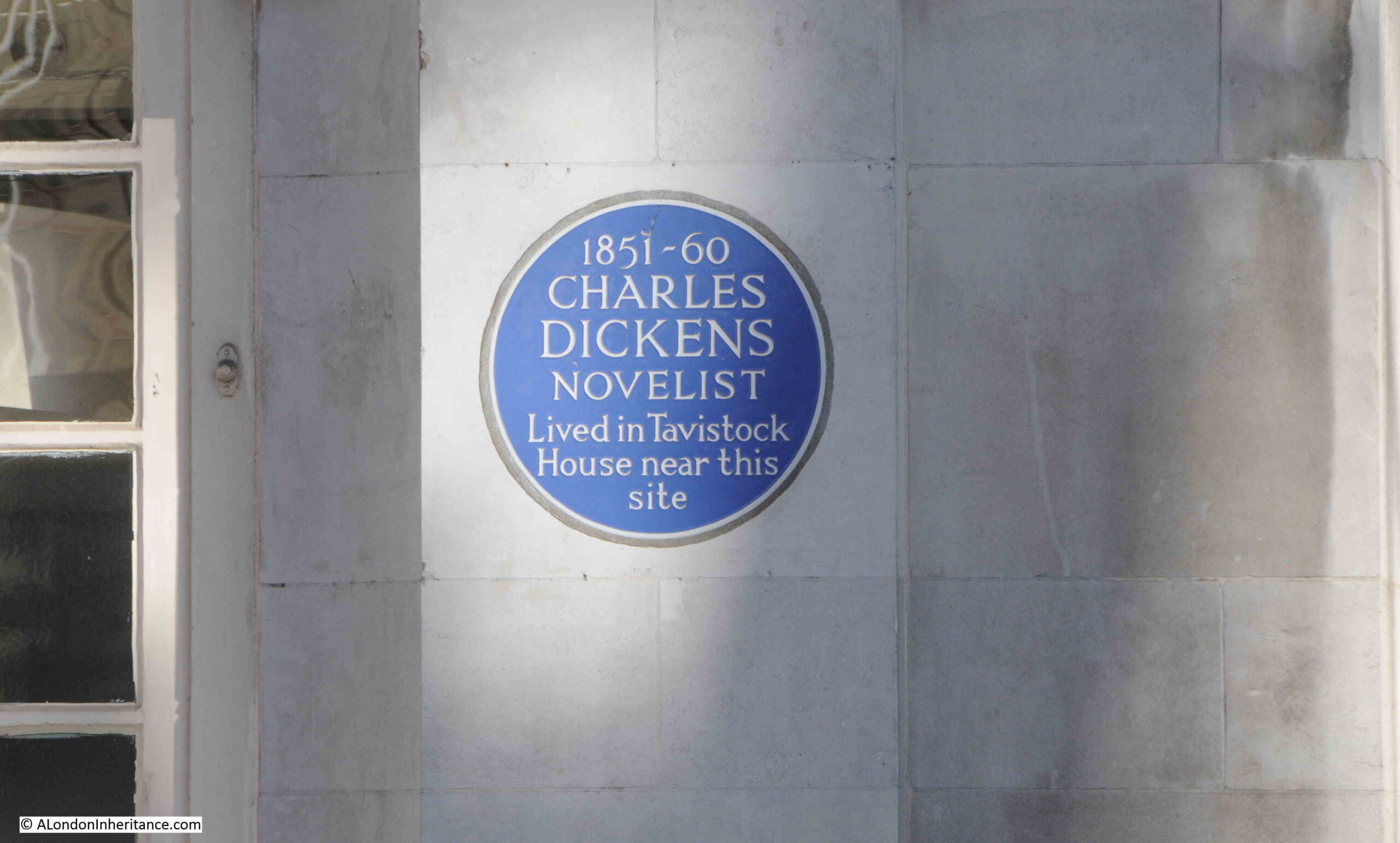

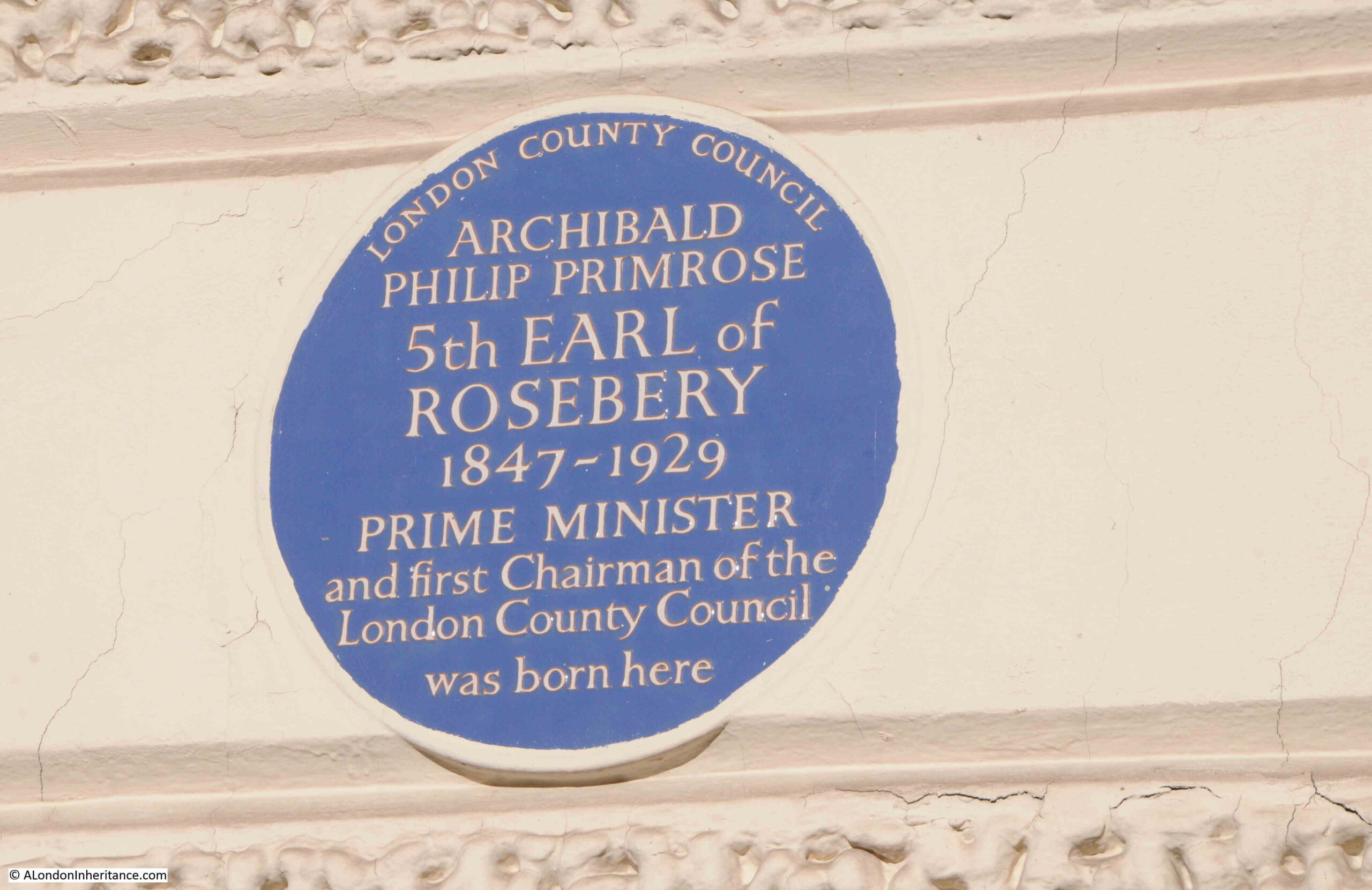

The house on the left has a Greater London Council blue plaque recording that Benjamin Waugh, the founder of the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children lived in the house:

Again, the houses in the above photo are listed, and looking further along the street there is another house with a tall, central bay running up all three floors.

There is enough in Crooms Hill to fill an entire post, and one of the buildings in the street houses the Fan Museum, however the Architects’ Journal map included more streets to the west of Greenwich Park, so I turned down King George Street to find more of the buildings marked on the map.

King George Street

The houses to the west are generally smaller. Those on Crooms Hill were facing Greenwich Park, and were the first buildings in this part of Greenwich. They were larger, and in a better position and were therefore built and occupied by the more wealthy residents of Greenwich. As we head into the streets to the west, we find houses that were built from the late 18th century onwards and were probably for the working class, tradesmen and those who worked in the many river related professions.

This large three storey building stands out along the terrace of two storey houses. Whilst it is now a private house, it was once a pub – the Woodman:

And almost opposite the Woodman is another closed pub. This one looking more like a pub. This was the Britannia:

Hidden behind the terrace houses on King George Street is a large, 19th century school, one of the impressive schools built by the London Schools Board. There is an entrance to the school playground from King George Street, with separate entrances for Girls & Infants, and for Boys:

Whilst the main school building behind is still a school, it looks as if the old entrance has been converted to residential.

Half way along King George Street is Royal Place, which has two storey workman’s houses on one side, and three storey, presumably more expensive houses on the opposite side:

At the end of Royal Place, we come to:

Royal Hill

And turning left along this road, we find a pub that is still open – the Prince of Greenwich:

The Prince of Greenwich is not the original name of the pub, it was originally the Prince Albert, and the street Royal Hill has an interesting history. It was originally Gang Lane, but renamed Royal Hill after Robert Royal, the builder of a theatre in Greenwich in 1749.

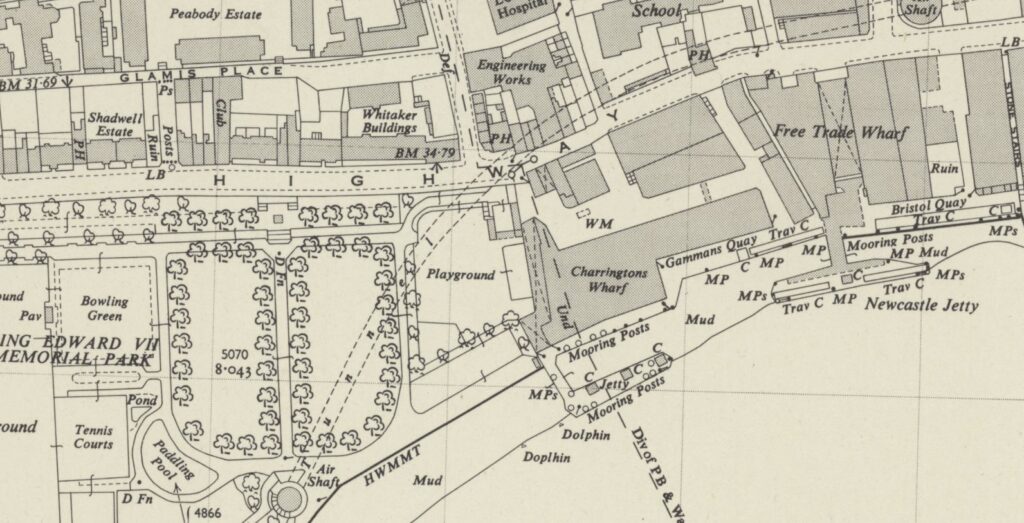

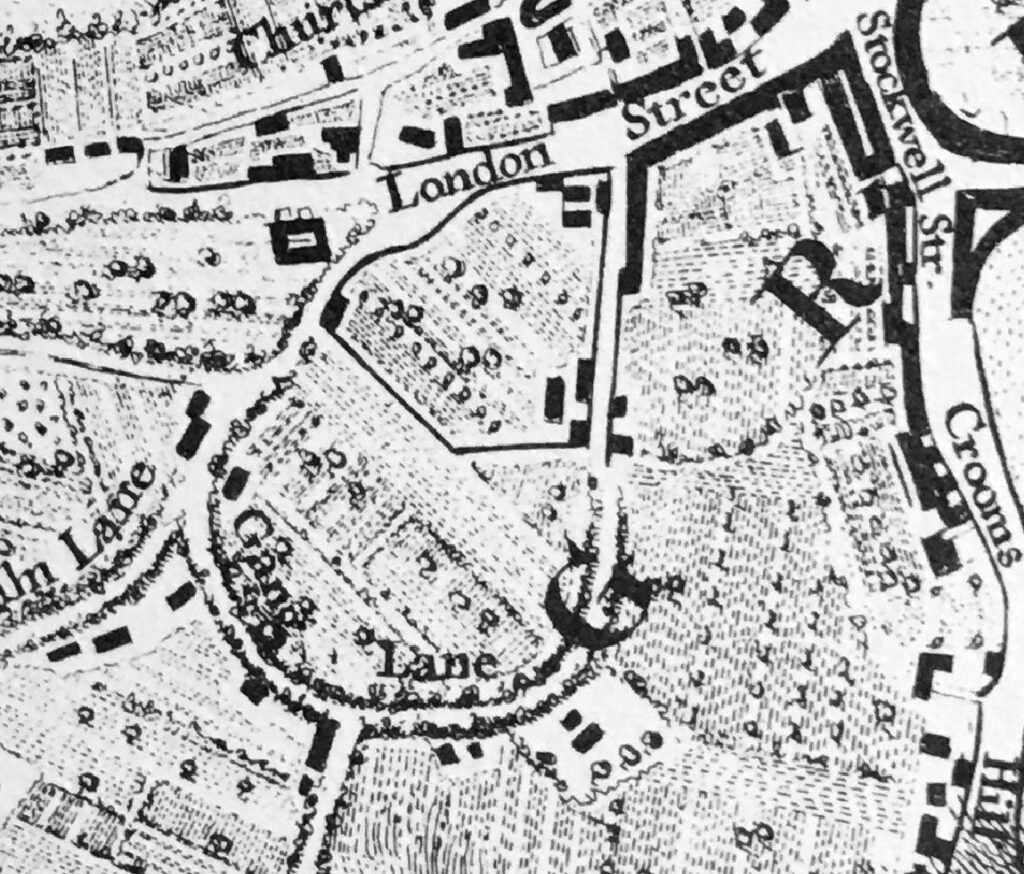

The street, Gang Lane is shown in Rocque’s map below, and is believed to date from the medieval period:

In the above map, it is shown running from London Street, then curving round to Lime Kiln Lane. Today, only the section to the right of the “L” in Lane remains, and to the west, the street now continues as a straight street, rather than continuing the curve.

Terrace houses in Royal Hill:

Along Royal Hill is another closed pub, the Barley Mow, although rather than residential, after closure in 2003, it was converted into a restaurant:

Above the main corner door is a lovely mosaic sign which dates from the time of the Barley Mow, with the Whitbread brewery name at the top and the pub name at the bottom, with presumably what was meant to be a stack of barley as the main feature:

After the Barley Mow pub, the buildings become more recent, although there is a stub of Royal Hill to the right with buildings from the 19th century, but here I turned around and headed back as there was still much to find from this section of the Architects’ Journal map.

Further back along Royal Hill, is another pub, thankfully still open. This is the Richard 1st, and comprises the two lime green buildings and the slightly taller building to the left. The pub dates from around 1843:

Going back to the Architects’ Journal map, and to the west of the park, there is a longer, slightly curvered section where the houses have been marked in black:

This is leading off Royal Hill and is:

Gloucester Circus

Large building with full height bay to the rear at the western end of Gloucester Circus:

As can be seen in the Architects’ Journal map, the highlighted section is along the south east side, with an open space in the middle, and unmarked buildings to the north west of the open space.

View along Gloucester Circus from the southern end, near Royal Hill:

The development of his area was in two stages. The curved terrace shown in black was built by Michael Searles and completed between 1791 and 1809. This work included the gardens in front of the terrace.

In the 1840s, a terrace was added along the other side of the gardens, and the curved terrace was known simply as The Circus, and the 1840s terrace as Gloucester Place.

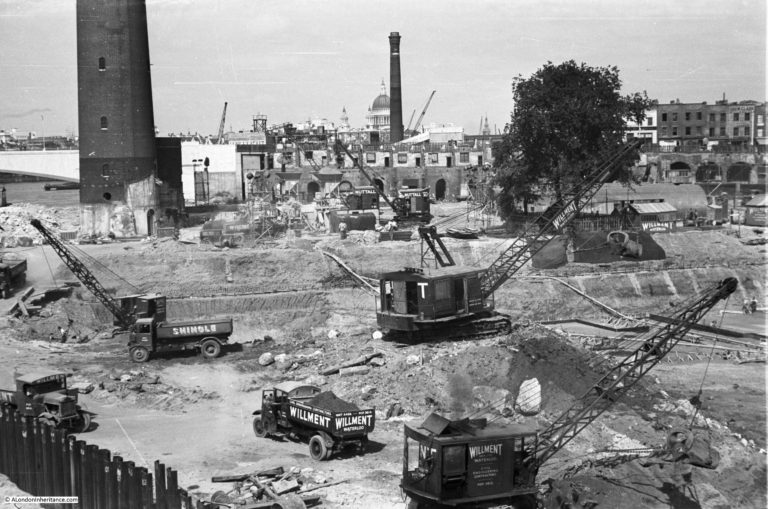

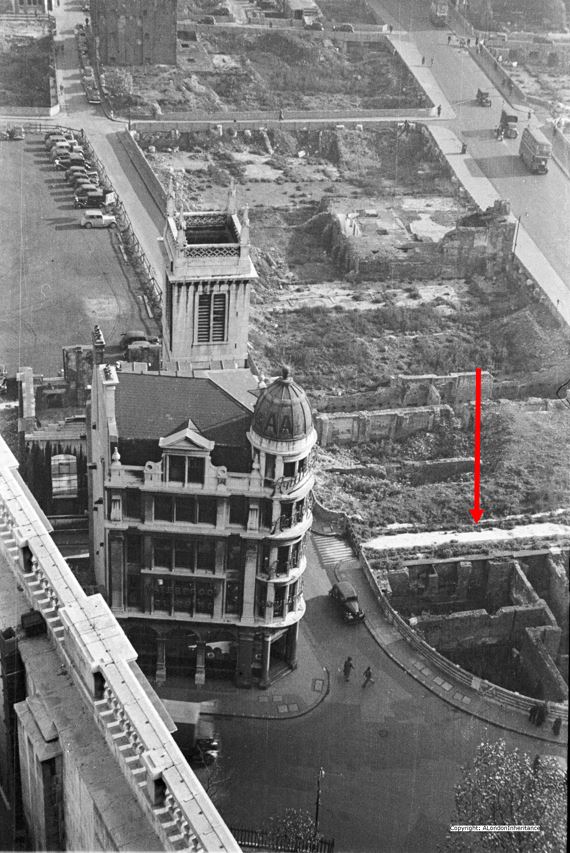

Wartime bombing resulted in the destruction of the 1840s terrace which is why there is post war building along this stretch with the Maribor Estate, named after Maribor in Slovenia, one of the three towns that Greenwich is twinned with.

There was also damage to the curved section, the Circus, including considerable damage requiring a rebuild to part of the central section.

The houses damaged during the war were rebuilt in the same style, but the difference can be seen today by the different coloured brick of the original and post war building work:

The terrace is Grade II listed, and is a lovely example of a late 18th / early 19th century terrace design and construction.

Renaming of all the buildings around the central gardens as Gloucester Circus came in 1938. The northern end of the curved terrace:

View along the central residents gardens, the curved terrace is to the left, and the post war buildings following bomb damage are to the right:

And at the end of Gloucester Circus, I have almost come full circle as I am back at Crooms Hill, and at the junction between the two streets is this large Grade II listed building:

Built during the late 18th century, there has been some significant rebuilding of the upper floors.

The chimney stack along the Gloucester Circus side of the house has a nice feature which my father photographed in the 1980s:

The Circus – the original name of the curved terrace that is now part of Gloucester Circus.

And that was just the western section of the Architects’ Journal map.

It is strange to consider that in the early 1970s, places such as these buildings and streets to the west of Greenwich Park were considered at risk from redevelopment, but London was a very different place then.

With the closure of the docks, loss of industry, population reducing considerably after the war, so much of east London was becoming derelict, and the vision to see what these places could really become was not, with some exceptions, really there.

So many lovely 18th and 19th century buildings were demolished in the post war period, and it is good too see places such as Greenwich, where they have survived as whole streets, rather than isolated blocks.

In part two, I will be following the Architects’ Journal map, heading towards the area of Greenwich around the Cutty Sark, then along the river to the streets surrounding the power station where there are some gems to be found.